Introduction

On 15 April 2023, Tomiwa Owolade penned an article for The Guardian titled "Racism in Britain is not a black and white issue. It's far more complicated". The piece challenged prevailing narratives about racism in Britain, drawing on recent survey data to argue for a more nuanced understanding of racial inequality. Owolade's core argument was that the common progressive view that "white people can't be victims of racism" is overly simplistic and inaccurate. He highlighted survey findings that complicate the typical narrative of racial inequality in Britain. Notably, the data showed that two-thirds of ethnic minority people have not experienced racist abuse, and that groups often considered "white" (such as Gypsy, Traveller, Roma, and Jewish people) report the highest rates of experiencing racist abuse.

The article also pointed out significant differences in reported experiences of racism within broad racial categories, such as between Black Caribbean and Black African people. Surprisingly, the survey found that White Irish people report experiencing more prejudice than some Black and Asian groups. Owolade argued for a more comprehensive and subtle approach to understanding and addressing racial inequality, rather than relying on oversimplified models of racism. He emphasised that while racial inequalities do exist in British society, the experiences of ethnic minorities are diverse and cannot be reduced to a single narrative. The piece challenged readers to either reconsider their understanding of racism based on this new data or to discard the report as unreliable, arguing that one cannot simultaneously accept the report's findings and maintain a narrow view of racism.

In my view the point made by the article has long been understood by non-white people in England, the "No Blacks, No Irish, No Dogs" signs from the 1960s and 1970s raises a compelling critique of the article's approach to discussing race and racism in Britain. This historical context, which united Blacks, Irish, and even dogs in a shared experience of discrimination, suggests that the struggle against prejudice has long transcended simple phenotypical racial categories. This perspective I believe challenges Owolade’s central argument and reveals potential shortcomings in his call for a more nuanced view.

While advocating for a more complex understanding of race and racism, he appears to fall short of fully embracing the historical nuances that have long been part of this discourse. By focusing primarily on contemporary survey data and current debates, the article overlooks crucial historical evidence of how discrimination has operated across various groups. This oversight suggests a gap in considering the shared experiences of discrimination that have historically transcended simple racial categories.

Furthermore, he seems to maintain a relatively rigid distinction between racial discrimination and other forms of prejudice, which this historical example directly challenges. This inconsistency in approach undermines the article's call for greater nuance. The omission of examples like the "No Blacks, No Irish, No Dogs" signs represents a missed opportunity to demonstrate how discrimination has historically operated in ways that complicate straightforward racial categorisations. His article might also be guilty of presenting historical views on race too simplistically, not fully acknowledging the complexities that existed even in earlier periods. This oversimplification of past understandings contradicts the call for a more nuanced contemporary view. There's a potential contradiction in advocating for nuance while not fully engaging with the historical nuances that have long existed in discussions of race and discrimination. My point is that the call for nuance in understanding race and racism should extend to historical analysis as well. The shared struggles of groups like Black and Irish people in the 1960s and 1970s demonstrate that the complexity in race relations and discrimination is not just a modern phenomenon but has deep historical roots.

This critique suggests that to truly achieve a nuanced understanding of race and racism in Britain, one must engage more deeply with historical examples that challenge straightforward racial categorisations. It also implies that the writer, while making important points about the complexity of contemporary racial issues, may not have fully applied this nuanced approach to historical context. In essence, there is a potential blind spot in Owolade's analysis, demonstrating that the call for nuance in discussing race and racism needs to be applied not just to current data, but also to our understanding of historical patterns of discrimination and solidarity. This historical perspective adds depth to the discussion and underscores the long-standing complexity of race relations in Britain, a complexity that his article, despite its intentions, does not fully capture.

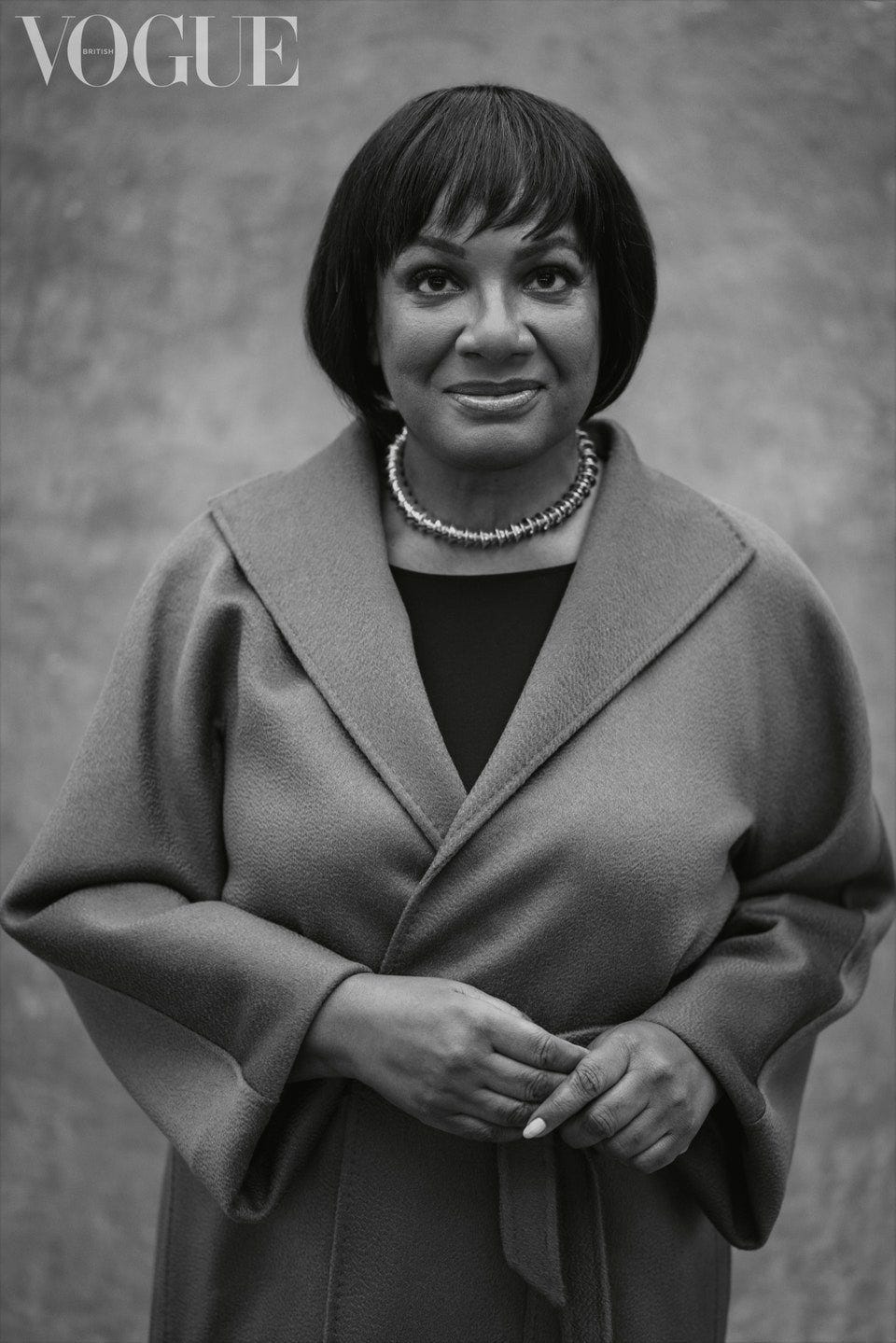

Diane Abbot weighs in

In response to this article, Diane Abbott, the long-time Labour MP for Hackney North, wrote a letter to The Observer. In her letter, Abbott acknowledged that "many types of white people with points of difference" can experience prejudice. However, she maintained that these groups are not subject to racism "all their lives".

Abbott's comments sparked controversy, leading to a swift backlash. In response, she later tweeted to withdraw her remarks and apologised "for any anguish caused". Starmer’s Labour Party deemed her comments "deeply offensive and wrong" and subsequently suspended the whip, meaning Abbott would no longer be allowed to represent Labour in the House of Commons and would instead sit as an independent MP.

This incident underscores the complexity and sensitivity surrounding discussions of race and racism in Britain. It highlights the challenges in reconciling traditional understandings of racism with emerging data and perspectives, as well as the political risks involved in engaging with these debates in the public sphere.

Was she really wrong?

Historically, race has been primarily associated with observable physical characteristics such as skin colour, facial features, and hair texture. However, contemporary scholarship recognises race as a social construct rather than a biological reality, with the boundaries between races often blurry and subject to change over time.

There is an ongoing discussion about whether racism should be defined solely based on racial prejudice or if it should also encompass systemic power dynamics. Abbott's initial statement acknowledged that white people can face prejudice but suggested this is not equivalent to the lifelong, systemic racism experienced by non-white people. This perspective aligns with a common contemporary academic and activist view of racism.

The question of whether Abbott was "wrong" depends largely on how one defines racism. If racism is understood purely as prejudice based on racial characteristics, her statement could be seen as inaccurate. However, if racism is defined as including systemic power dynamics, her statement aligns more closely with this definition, though it may still fail to account for the experiences of all groups.

Double standard

The controversy surrounding Diane Abbott's comments and subsequent retraction raises thought-provoking questions about the nature of discourse on race and racism in contemporary British society. There is a possibility of a double standard at play, where certain viewpoints on race and racism are more readily accepted in mainstream discourse, while others are swiftly denounced.

The quick retraction and apology by Abbott might suggest a pressure to conform to certain narratives about race and racism, potentially discouraging open debate on these complex issues. This situation occurs against the backdrop of a prevailing narrative in many circles that racism primarily affects non white people and that White people, as a group, cannot experience racism due to their societal privilege. That is what White privilege really means.

However, the survey data presented in Owolade's article complicates this narrative, which might make some uncomfortable with its implications. This discomfort highlights the ongoing debate about whether political correctness enhances respectful discourse or stifles open dialogue, particularly on sensitive topics like race.

The swift backlash and Abbott's quick retraction could be seen as evidence of a bias against viewpoints that challenge the prevailing narrative.

Diane Abbott's original statement demonstrated a nuanced understanding of the complexities surrounding these issues. She acknowledged that "many types of white people with points of difference" can experience prejudice, while arguing that they don't experience racism "all their lives". This careful distinction between racial and ethnic discrimination aligns with a historically grounded understanding of race. Abbott appears to have used the traditional definition of race, based primarily on physical characteristics like skin colour, which has been the predominant understanding for much of modern history in legal and sociological contexts. Her statement is consistent with this view, distinguishing between prejudice, which White ethnic groups can face, and racism as experienced by non-whites.

This perspective aligns with many academic and activist definitions of racism as "prejudice plus power", acknowledging systemic factors beyond individual prejudice. Abbott's nuanced point recognises different forms of discrimination while maintaining a distinction between ethnic prejudice and racial discrimination. The backlash and subsequent retraction may reflect several factors: a misunderstanding of Abbott's nuanced point, a conflation of ethnic and racial discrimination in public discourse, and political pressure to adhere to certain narratives about racism

My analysis suggests that Abbott's original statement was more accurate and carefully considered than the Labour’s reaction might have indicated. It's possible to interpret this situation as an example of mainstream discourse shutting down a viewpoint that challenges the established narrative on racism. The quick retraction could be seen as an attempt to avoid further controversy rather than engage in a substantive debate about the complexities revealed by the survey.

Take up the White man’s Burden

The historical context provided by Rudyard Kipling's poem "The White Man's Burden", published in 1899, offers a valuable lens through which to view these events. In Kipling's era, at the height of European colonialism, "white" was unambiguously used as a racial category, with the poem explicitly framing the world in terms of white and non-white races. During this period, the concept of race was much more rigid and was considered a biological reality. "White" specifically referred to people of European descent, and this racial categorisation was used to justify colonial practices and racial hierarchies. This stands in stark contrast to our modern understanding, where we recognise race as a social construct rather than a biological fact, with contemporary scholarship emphasising the fluidity and cultural construction of racial categories.

The evolution of racial categories is evident in how groups that might have been considered non-white in Kipling's time, such as Irish or Southern Europeans, are generally considered white today. This shift underscores the malleability of racial classifications over time.

While the article and survey discussed in Owolade's piece deal with contemporary understandings of race and ethnicity, which have evolved significantly since Kipling's time, the legacy of these historical racial categorisations continues to influence current discussions and perceptions. Kipling's explicit focus on race, and specifically on white people as a distinct racial group, highlights how much our understanding of race has changed over time, yet also demonstrates the persistence of certain categorisations.

Irony

To my mind, the censure of Diane Abbott, a prominent black woman in British politics, for using a historically grounded definition of race was unfair. Abbott's original statement carefully distinguished between racial and ethnic discrimination, aligning with the traditional understanding of race based primarily on physical characteristics like skin colour. This view has been the predominant understanding for much of modern history, including in legal and sociological contexts. Her nuanced point recognised different forms of discrimination while maintaining a distinction between ethnic prejudice and racial discrimination.

The swift backlash and Abbott's subsequent retraction could be interpreted as an exercise of power by the political and media establishment, effectively silencing a perspective that, while controversial, is rooted in a historically understood concept of race. This raises questions about who gets to define and shape the discourse on race and racism in contemporary Britain.

The irony of a black woman being labelled racist for expressing views consistent with long-standing definitions of race is not lost in this situation. It underscores the dishonesty surrounding discussions of race in modern society, where evolving understandings clash with historical perspectives.

Furthermore, this incident highlights a potential double standard in how different voices are treated in discussions about race. Abbott, as a black woman, might be expected to have particular insight into issues of race and racism. Yet, her perspective was swiftly denounced, raising questions about whose voices are privileged in these debates and why. It highlights the tension between evolving understandings of these concepts and their historical roots, and raises important questions about power, representation, and the boundaries of acceptable discourse in conversations about race. The censure of Abbott for expressing a view consistent with historical understandings of race indeed seems to demonstrate an exercise of power that warrants critical examination.