This is the first in a five-part series - Reclaiming the Radical Black Intellectual Tradition - that explores the lives and ideas of extraordinary intellectuals whose contributions to Black liberation thought deserve far greater recognition than mainstream historical narratives typically afford them. Through examining W.E.B. Du Bois, George Padmore, C.L.R. James, Claudia Jones, and the Dar es Salaam School, I aim to illuminate the interconnected web of radical thinking that shaped anti-colonial and Pan-Africanist movements across three continents.

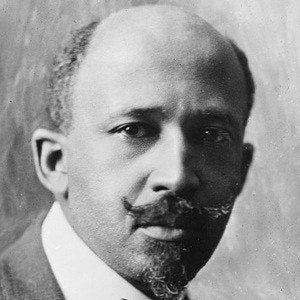

W.E.B. Du Bois: The Global Intellectual

WEB Du Bois is my kind of intellectual. Most people know Du Bois for his idea of "double consciousness" - the feeling African Americans have of seeing themselves through both their own eyes and the eyes of a racist society. But focusing only on this concept misses the bigger picture of who Du Bois really was, a global thinker who helped connect liberation movements around the world.

Beyond America's Borders

Du Bois famously said that "the problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the colour-line." But he wasn't just talking about America. While other civil rights leaders focused on domestic issues, Du Bois saw that racial oppression was a global system. He understood that what happened to Black Americans was connected to what was happening to colonised people in Africa, Asia, and the Caribbean.

This global perspective made him unique. He became one of the first people to build international networks of activists and intellectuals who were all fighting the same basic fight against racial oppression, just in different places. This is why he is my kind of intellectual - the capacity to see beyond immediate borders and to conceptualise issues globally.

Building Connections Across Continents

Between 1919 and 1945, Du Bois organised five Pan-African Congresses. These weren't just conferences, they were groundbreaking attempts to create lasting connections between Black liberation movements around the world.

Think of it this way: before Du Bois, activists fighting colonialism in Africa might not have known about activists fighting racism in America or the Caribbean. Du Bois brought them together, creating a network that would prove essential when African countries started fighting for independence decades later.

The 1945 Manchester Congress was especially important. Du Bois, now 77 years old, was the elder statesman connecting an older generation of Pan-African thinkers with rising leaders like Kwame Nkrumah (who would become Ghana's first president) and Jomo Kenyatta (who would lead Kenya to independence). His presence gave legitimacy to their more radical anti-colonial ideas, while their energy reinvigorated his own commitment to global struggle.

The Caribbean Connection

Du Bois had a special relationship with Caribbean intellectuals that reveals another side of his global vision. Despite sometimes disagreeing with Marcus Garvey, he recognised his importance. He worked closely with brilliant thinkers from Trinidad like George Padmore and C.L.R. James.

Du Bois understood something that proved prophetic: small Caribbean islands were producing some of the most influential global thinkers of the century. He saw that intellectual leadership could come from unexpected places within the African diaspora.

The Data-Driven Scholar

Here's something most people don't know about Du Bois: he was a pioneering economist who used hard data to fight racism over a century before it became fashionable.

His 1899 study The Philadelphia Negro was revolutionary. Du Bois didn't just theorise about poverty - he counted it. He went door-to-door in Philadelphia's Seventh Ward, documenting the economic conditions of Black residents. He then compared his findings to similar studies of poor people in London.

What he found contradicted the racist explanations of his time. His data showed that 8.9% of Black households were "very poor" and 57.4% were "poor," but this wasn't because of any personal failings. Du Bois showed that a Black person earning $1,500 a year (good money at the time) still had to spend more than white neighbours on rent, clothing, and entertainment just to maintain the same standard of living. In other words, Du Bois used numbers to prove what we now call "the Black tax," the extra costs of being Black in America. He was doing this kind of analysis over 100 years before economists started calling it stratification economics.

From Liberal to Radical

Du Bois's thinking evolved over his long life. He started as a liberal who believed education and hard work could overcome racism. But as he gathered more evidence and witnessed more injustice, he became convinced that the problem was deeper, it was built into the economic system itself.

This evolution influenced many of the younger thinkers he mentored. His later embrace of socialist ideas provided theoretical foundation for people like George Padmore, who evolved from communist to Pan-African socialist. His analysis of how global capitalism depends on racial exploitation influenced Walter Rodney, whose book How Europe Underdeveloped Africa became a classic of African liberation thought.

Double Consciousness Goes Global

When you understand Du Bois's global perspective, even his famous concept of double consciousness takes on new meaning. It's not just about individual psychology; it’s about the structural position of colonised peoples everywhere. The "two-ness" he described - seeing yourself through both your community's eyes and your oppressor's eyes - mapped onto the economic position of colonised peoples around the world. They were simultaneously inside capitalist systems (as workers and consumers) but excluded from the benefits (as non-citizens and "inferior" beings).

Why This Still Matters

Du Bois's framework for understanding what we now call "racial capitalism" remains strikingly relevant today. His analysis of how psychological oppression works alongside economic exploitation helps us understand persistent global inequalities. While mainstream economics often attributes inequalities to individual choices or market forces, a Du Boisian analysis looks at how historical processes of racial exploitation continue shaping outcomes today through institutions and psychological inheritance.

Students today who struggle with economic theories that ignore their lived experiences face their own form of double consciousness, forced to see themselves through frameworks that make their communities invisible.

The Unfinished Project

Perhaps Du Bois's greatest insight was recognising that intellectual work and political organising aren't separate activities. His scholarship always served liberation movements, while his organising was informed by rigorous analysis. This integration influenced everyone who followed in his footsteps. From George Padmore's analysis of decolonisation strategies to Amílcar Cabral's development of "the weapon of theory," these thinkers understood that theoretical understanding must emerge from and respond to real historical conditions.

Du Bois understood that achieving true liberation required addressing both external structures of oppression and their internalised psychological effects. His vision of education as consciousness-raising anticipated Paulo Freire's critical pedagogy, while his analysis of global capitalism prefigured dependency theory and world-systems analysis.

Legacy for Today

As we continue grappling with global inequalities that reproduce colonial hierarchies in new forms, Du Bois's approach offers essential resources. His life's work demonstrates that meaningful change requires not just new policies but fundamental transformation of how we understand economic relationships and human possibilities.

In examining overlooked contributions to Pan-African thought, Du Bois emerges not merely as the "Father of Pan-Africanism" but as the intellectual architect who designed frameworks strong enough to support generations of global liberation movements. His true legacy lies not in any single concept but in showing us that rigorous scholarship, international solidarity, and grassroots organising must work together as integrated elements of transformative social change.

References

Du Bois, W.E.B. (1933) On Being Ashamed of Oneself: An Essay on Race Pride, Crisis, 40(9). Available at: https://www.dareyoufight.org/Volumes/40/09/on_being_ashamed.html (Accessed: [20 April 2025]).

Du Bois, W. E. B. (2016) The Souls of Black Folk. Dover Thrift Editions.

Numa, G. and Zahran, S. (2025) W. E. B. Du Bois and Economics: A Reappraisal, Journal of Economic Literature, forthcoming.

Looking forward to this series.

Love the analysis of the implications for today’s scholars and advocates. Becoming familiar with double consciousness can energize anti racist movements and the work of social justice change agents.

Very well written. Du bois was without a doubt the doyen of his time.