Introduction

Cedric Robinson's Black Marxism demonstrated that capitalism emerged as a racialised continuation of feudalism rather than a radical break from it. European feudal society had developed sophisticated forms of racial hierarchisation, targeting Slavs, Roma, and Irish populations before African chattel slavery. This racialised feudal order provided the foundational logic for modern capitalism, which globalised these hierarchies through colonialism and slavery.

The British monarchy and its estates illustrate this continuity between feudal racialisation and modern capitalism. These institutions, which once established colonial exploitation through enterprises like the Royal African Company, now operate through market mechanisms that perpetuate historical patterns of privilege and exclusion.

The Code of Britain

Britain's contemporary global position relies on its sophisticated legal-financial architecture, representing its primary form of power in the 21st century. This code, accumulated through centuries of imperial governance and commercial dominance, manifests in Britain's remarkable capacity to export legal and consulting services globally.

Britain's contemporary exceptionalism lies in its mastery of lawfare - the deployment of legal mechanisms as instruments of power. This expertise emerged from centuries of colonial administration, where British law served as both the framework for imperial governance and the mechanism for wealth extraction.

The City of London exemplifies this evolution from medieval merchant settlement to global nexus of legal-financial expertise. Its network of tax havens, termed 'offshore financial centres', represents the globalisation of British legal expertise, creating spaces of exception that mirror medieval privileges granted to royal chartered companies.

Understanding Britain's code reveals how historical advantages transform into contemporary power. Cracking the code of Britain means recognising how seemingly neutral legal and financial arrangements mask the continuation of colonial-era patterns of extraction and privilege, particularly in how these mechanisms concentrate wealth in historically advantaged institutions while depleting resources from public services that serve marginalised communities. The legal mechanisms developed to manage empire have evolved into sophisticated tools for maintaining economic advantage in a globalised world.

The Modern Face of Royal Privilege

The modern British monarchy presents itself as a ceremonial institution, yet royal estates operate as examples of 'crack-up urbanism' - the splitting of cities into zones under different rules. London's Battersea Power Station development, where a £9 billion project secured special permissions to reduce its affordable housing commitment from 35% to 9%, demonstrates this phenomenon.

The Church of England offers a meaningful primary comparison, holding approximately 200,000 acres across England. While it retains certain historical privileges like the royal estates, the differences are telling. The Church Commissioners must pay corporation tax on their commercial activities and face thorough scrutiny through the Charity Commission. They maintain a published ethical investment policy with specific social responsibility commitments, including a requirement to provide 30% affordable housing on residential developments.

Oxford and Cambridge Universities together control about 126,000 acres of land and property. These ancient institutions operate under notably different constraints than royal estates. They pay corporation tax on commercial activities and must demonstrate public benefit to maintain charitable status. Their operations face regular scrutiny from the Office for Students, with more transparent accounting requirements and adherence to standard planning regulations without special exemptions.

The National Trust presents another illuminating comparison with its 610,000 acres. Despite its charitable status, it pays VAT and operates under strict public access requirements. The Trust must reinvest proceeds into conservation, provide detailed public reporting on its finances and activities, and follow standard planning processes like any other organisation.

These comparisons reveal several distinctive features of royal estate holdings. They enjoy unique tax privileges without corresponding public benefit requirements and operate under less rigorous transparency requirements. They maintain greater flexibility in negotiating planning obligations, face no formal requirement to demonstrate social value, and experience limited external oversight of commercial activities.

The financial implications become particularly evident when examining rental practices. While other institutional landlords typically align with market rates, the royal estates often secure above-market returns from public sector tenants. Where other large landowners face pressure to demonstrate social value, royal estates operate with fewer constraints. Standard institutional landlords generally cannot negotiate reduced affordable housing requirements with the same effectiveness.

The numbers tell their own story. The Church Commissioners returned £312.4 million to support Church activities in 2022. Oxford's endowment produced £255.8 million in 2022, while the National Trust's commercial income reached £148.4 million in 2022. Yet each of these institutions faces more stringent oversight and public benefit requirements than royal estates, despite generating comparable revenues.

This comparative analysis reveals that royal estates occupy a unique position amongst UK institutional landholders, maintaining privileges that exceed those granted to other historically significant institutions. The absence of equivalent oversight or social benefit requirements sets them apart in modern Britain's institutional landscape.

Colonial Origins and Contemporary Wealth

The royal estates' wealth traces directly to Britain's colonial project. Elizabeth I's provision of royal ships for Sir John Hawkins' first slave-trading expedition in 1562 established royal involvement in colonial exploitation. The Royal African Company, established by Charles II, transported more enslaved Africans to the Americas than any other institution in the Atlantic slave trade.

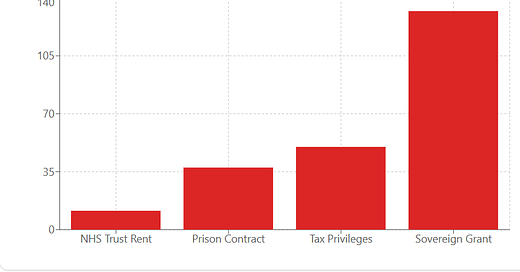

Today, the Duchies of Lancaster and Cornwall extract millions from public services while maintaining tax privileges. The Duchy of Lancaster charges £11.4 million in rent to Guy's and St Thomas' NHS Trust for warehouse space, while the Duchy of Cornwall holds a £37.5 million contract with the Ministry of Justice for Dartmoor Prison. This £11.4m could fund 285 nurses' salaries, purchase 3-4 MRI machines, or provide 7,600 hospital bed days.

These financial extractions disproportionately affect Black communities through their impact on NHS resources. Research consistently shows that Black people in Britain face significant health inequalities - including higher rates of diabetes, hypertension, and mental health challenges - while simultaneously experiencing longer waiting times and reduced access to preventive care. When NHS trusts must allocate millions to royal estate rents, it diminishes their capacity to address these documented health disparities. The areas served by Guy's and St Thomas' Trust include significant Black populations in Southwark and Lambeth, meaning that royal privilege directly impacts communities whose ancestors' exploitation helped build that very privilege. This creates a perverse cycle where historically marginalised communities continue bearing the financial burden of institutional arrangements that originated in their exploitation.

The Mechanics of Modern Privilege

The estates employ lawfare - using legal and administrative processes to maintain historical advantages. While claiming to operate as commercial entities, they retain exemptions from corporation tax and capital gains tax. The scale reaches approximately £50 million in 2023 alone.

The defence that these estates receive no direct taxpayer funding requires examination. They benefit from:

Income from taxpayer-funded public services

Tax exemptions providing competitive advantages

Historical land holdings acquired through centuries of privilege

Additional income through the Sovereign Grant (£132 million in the coming year)

Conclusion

The operations of Britain's royal estates reveal how crack-up urbanism, lawfare, and racial capitalism work together to preserve historical privilege in modern form. These mechanisms create protected enclaves where normal regulations can be negotiated away, while seemingly neutral administrative processes preserve historical advantages.

The £50 million flowing from public services to tax-privileged royal estates in 2023 demonstrates how financial arrangements continue concentrating wealth in institutions whose privileges originated in colonial exploitation. This system challenges us to reconsider how institutional privilege operates in contemporary society and what meaningful reform would require.