Introduction

In the labyrinthine world of modern American politics, an unexpected thread has emerged, weaving together some of the most influential voices in right-wing politics through a shared historical connection: apartheid South Africa. This connection, whilst perhaps surprising at first glance, offers profound insights into the ideological underpinnings of certain strains of contemporary American political thought.

Consider this remarkable convergence: Elon Musk, the world's wealthiest man and now owner of X (formerly Twitter); David Sacks, a prominent venture capitalist and Trump fundraiser; Peter Thiel, the influential tech investor and political kingmaker; and Paul Furber, allegedly connected to the origins of QAnon. These four men, all in their fifties, share more than their current influence on American politics, they share formative experiences in apartheid-era South Africa.

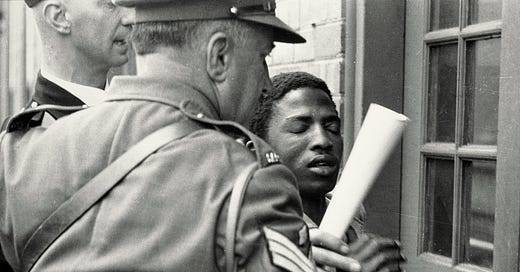

Photo: Peter Magubane

The Shadow of Apartheid

The significance of this connection extends far beyond mere coincidence. Apartheid South Africa represented an extreme version of societal dynamics that eerily parallel current American political debates. The system was characterised by stark inequality, rigid social hierarchies, and a particular worldview that naturalised these disparities.

Take Peter Thiel's early experiences. His father worked at a uranium mine where the contrast between white managers and Black workers was stark and institutionalised. White staff enjoyed country club memberships and modern medical facilities, whilst Black workers were confined to labour camps. This environment didn't just demonstrate inequality, it normalised it.

The Libertarian Connection

Perhaps most intriguingly, these experiences seem to have fostered a particular strain of libertarian thought. The dysfunction of the apartheid government, followed by the challenges of the ANC transition, appears to have catalysed a deep scepticism of governmental intervention in social issues. This mindset dovetails perfectly with certain aspects of American right-wing ideology, particularly its resistance to government-led efforts at addressing racial inequalities.

This connection becomes especially clear in early writings. In 1995, Thiel and Sacks co-authored "The Diversity Myth," a critique of multiculturalism that confidently declared the virtual non-existence of racism among younger Americans. This perspective that racial inequality exists independent of systemic racism bears striking similarities to arguments used to justify apartheid's inequalities as natural rather than manufactured.

Understanding Through Racial Capitalism

These connections become even more significant when viewed through the lens of racial capitalism. This theoretical framework, developed by scholar Cedric Robinson in his seminal work "Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition," helps us understand why these historical links aren't merely biographical curiosities but rather reflect deeper patterns in how capitalism operates.

Robinson's core insight was revolutionary: racism isn't incidental to capitalism but fundamental to its development and operation. He argued that capitalism emerged from the European medieval order already infused with racial thinking, and that racial identity and economic exploitation have always been intertwined. Through this lens, apartheid South Africa wasn't an aberration but rather an extreme expression of capitalism's inherent tendencies.

The Machinery of Digital Racial Capitalism

The mechanisms through which racial capitalism operates in the tech industry are both subtle and pervasive. Consider the venture capital funding process. Research shows that Black founders receive less than 1% of venture capital funding, yet this disparity is often justified through supposedly objective criteria like "track record" or "founder market fit." This mirrors how South African mining houses used apparently neutral language about "efficiency" and "skill" to maintain racial hierarchies in their workforce.

The tech industry's reliance on "warm introductions" and network-based hiring creates another mechanism for racial exclusion. Just as the South African mining industry relied on white social networks to maintain control of capital and management positions, Silicon Valley's emphasis on social capital often excludes those without access to predominantly white, elite networks.

Historical Echoes: From Mining Houses to Tech Campuses

The parallels between South African mining houses and modern tech companies run deeper than might first appear. The Anglo American Corporation, which dominated South African mining, operated what it called a "progressive" employment policy in the 1960s and 1970s. This policy claimed to be advancing Black workers whilst maintaining fundamental racial hierarchies, much like how modern tech companies often celebrate superficial diversity whilst maintaining structural inequalities.

The mining houses' compound system, which housed Black workers in controlled environments while providing recreational facilities and basic services, finds an eerie parallel in modern tech campuses. Today's tech campuses, with their free food, gyms, and leisure activities, similarly create controlled environments that mask fundamental labour inequalities.

Implications for Contemporary Inequality

Understanding tech's role in racial capitalism has profound implications for addressing contemporary inequality. Traditional diversity initiatives often focus on increasing representation without challenging the underlying structures that reproduce racial hierarchies. This approach parallels failed reforms in apartheid South Africa, which attempted to modify racial capitalism without fundamentally transforming it.

The persistence of racial capitalism in tech suggests that addressing inequality requires more fundamental changes:

The venture capital system itself needs restructuring. Just as the dismantling of apartheid required more than simply allowing Black South Africans to own shares in mining houses, addressing tech's racial inequalities requires more than simply encouraging venture capitalists to consider diverse founders. New funding structures, perhaps including public investment vehicles or cooperative ownership models, might be necessary.

Technical education and training systems need to be reconsidered. The current system, which often reproduces existing inequalities through expensive coding bootcamps and selective university programmes, parallels how the South African mining industry used training programmes to maintain racial hierarchies whilst appearing to offer advancement opportunities.

Breaking the Pattern

The connection between apartheid South Africa and modern tech capitalism offers both warnings and opportunities. It warns us that racial capitalism can adapt and reproduce itself even in supposedly progressive industries. But it also suggests possibilities for change. Just as the anti-apartheid movement eventually succeeded through a combination of internal resistance and external pressure, addressing racial capitalism in tech will most likely require both internal reform efforts and external regulatory and social movements. Real transformation requires engaging with how racial thinking remains fundamental to contemporary capitalism, particularly in its digital forms.

Full Circle: The Individual and the System

Returning to our original cast of characters, Musk, Thiel, Sacks, and Furber, we can now see them not merely as individuals shaped by their South African experiences, but as actors within a larger system of racial capitalism that has evolved from the mining houses of apartheid to the venture capital firms of Silicon Valley. When Musk warns about alleged "white genocide" in South Africa, when Thiel argues for the economic soundness of certain social hierarchies, when Sacks rallies against "wokeness" in tech, they are not simply expressing personal views shaped by their past. Rather, they are articulating and reinforcing patterns of thought that have long been central to racial capitalism's ability to reproduce itself across time and space.

Their individual successes in the American tech industry and their subsequent influence on right-wing politics demonstrate how racial capitalism can adapt and thrive in new contexts whilst maintaining its essential character. The fact that these four men, all shaped by apartheid South Africa, have become such influential voices in American tech and politics is not merely an historical curiosity. It is a testament to the persistent power of racial capitalism to reinvent itself, finding new expressions in each era whilst maintaining its fundamental logic of racial and economic hierarchy.

This Stack explores themes originally reported in the Financial Times (Simon Kuper, September 19 2024), expanded with additional context and analysis.