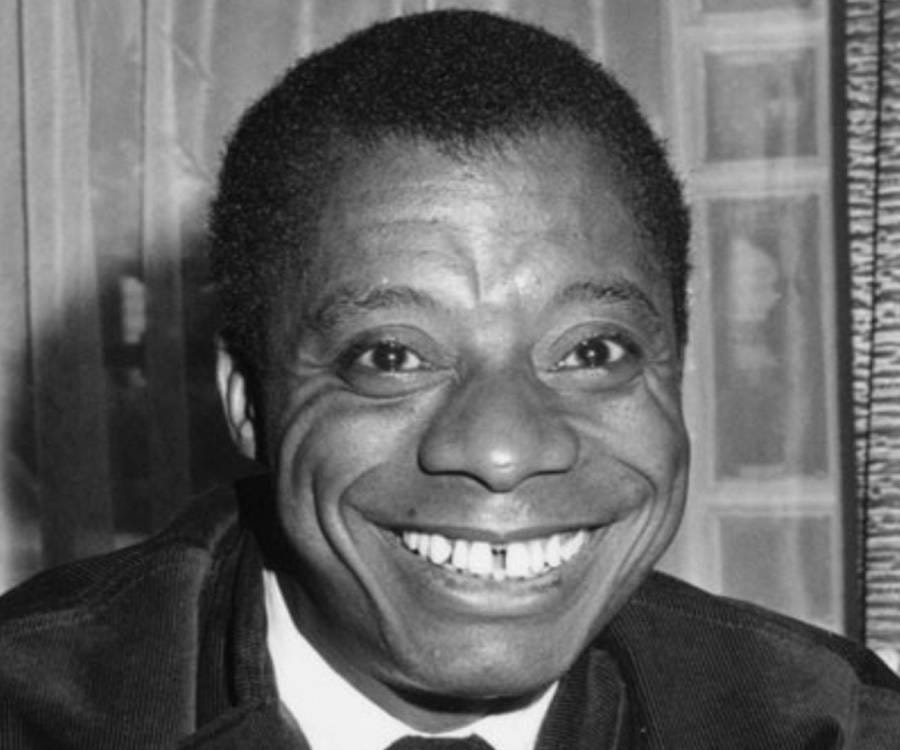

Throughout the month of August, I've been puzzled by the sudden surge of Baldwin articles everywhere I turn. Then it hit me - this is Jimmy Baldwin's centenary month. He would have been 100 on August 2nd, and for this reason, the whole world has chosen to remember Jimmy Baldwin. James Baldwin was born on August 2nd, 1924, he died on December 1st, 1987, and the world is a much poorer place without him.

I was 11 or 12 when I read my first Baldwin novel – 'Another Country'. Published in 1962, it's now considered one of his major works, exploring complex relationships across racial and sexual boundaries in New York City and France. My young mind didn't fully grasp the nuances, but there was something about the writing that I fell in love with.

I followed this up with 'The Fire Next Time' (which I understood better), 'Go Tell it on the Mountain, Notes of a Native Son, Giovanni’s Room, and Tell Me How Long the Train has been Gone. By the end of my teenage years, I had devoured every Baldwin novel I could find and one of the understandings that I came to was that if Baldwin was queer than queer people must be ok.

What I didn't know then, but find fascinating now, is that Baldwin had been a preacher in his teen years. In his essay "Letter From a Region in My Mind," he wrote about experiencing a "prolonged religious crisis" at fourteen. He described this time as "the most frightening time of my life, and quite the most dishonest." It's intriguing to think how this early experience with religion might have shaped his later writings.

Baldwin's work consistently tackled themes that defined his writing:

1. Race relations in America

2. Sexuality and sexual identity

3. The experience of being an expatriate

4. The complexities of human relationships

Every year, I return to Baldwin, re-reading many of the novels from my youth. It's his insight, his prose, and his analysis of race relations in the USA that I find so instructive. His work has given me a better understanding of myself, the human condition, and the world in general.

Baldwin's journey as a writer started when he was 10 years old when he encountered Dickens’ 'A Tale of Two Cities.' He was later to say, “… it wasn't the virtuous Charles Darnay or the heroic Sydney Carton who spoke to me. It was Thérèse Defarge, brimming with hate, knitting as the guillotine did its grim work.” He had been captivated by her unrelenting hatred, recognising it in the streets of Harlem. In the autobiographical note in Notes of a Native Son, he shares the following:

“I love America more than any other country in the world, and, exactly for this reason, I insist on the right to criticize her perpetually. I think all theories are suspect, that the finest principles may have to be modified, or may even be pulverized by the demands of life, and that one must find, therefore, one’s own moral center and move through the world hoping that this center will guide one alright. I consider that I have many responsibilities, but none greater than this: to last, as Hemingway says, and get my work done. I want to be an honest man and a good writer.”

This is where I believe that many people go wrong. They believe that because they love their countries, because they are ‘patriots’ they can never criticise them. So, they continuously extol the virtues of these countries, ignoring the obvious fault lines and attempt to perpetuate a false narrative of national exceptionalism. These people could learn from Baldwin and his honesty, if you love your country, and your flag, then you must of necessity criticise its faults - how else will the country improve? This to my mind is patriotism in its highest form, it is born of honesty.

Like many of us Balwin’s major influence in his early years was his teacher, Orilla Miller, who introduced him to a world of books and transformed his understanding of racism. "I read myself out of Harlem," Baldwin once said, acknowledging the power of literature in his life. Like Baldwin, I read my way out of Brixton, his words fired my imagination and allowed me to envisage what was beyond my immediate surroundings, so yes, I saw Brixton Prison, but I was able to see beyond it as well.

I've recently learned that the American Harlem Renaissance painter Beauford Delaney was another significant mentor to Baldwin. Baldwin met Delaney when he was just 15 and came to consider him both a great friend and a "spiritual father".

In 1948, Baldwin left America for France. He wanted to prevent himself from becoming "merely a Negro" and to discover how his unique experiences could connect him with others rather than divide him. In a 1984 interview with The Paris Review, Baldwin revealed a more personal reason for his departure: "My luck was running out. I was going to go to jail, I was going to kill somebody or be killed. My best friend had [died by] suicide two years earlier."

Baldwin's perspective on race evolved over time. In his early years, he believed that white people's actions weren't solely due to their race. As the hopeful spirit of the 1960s faded into the more sombre mood of the 1970s, Baldwin's writings reflected a shift. The loss of civil rights leaders, the turmoil in urban areas, and the stubborn persistence of racial inequality all contributed to a more sobering perspective in his later works. Reading these later pieces, I could feel the weight of disillusionment in his words, a far cry from the cautious optimism of his earlier writings.

What I find particularly interesting is Baldwin's versatility as a writer. He wasn't just a novelist; he was also a film critic. In his book-length essay "The Devil Finds Work," he wrote about American cinema, particularly interested in what it had to say about race. His critique of 'The Exorcist' is particularly poignant: "The mindless and hysterical banality of evil presented in The Exorcist is the most terrifying thing about the film. The Americans should certainly know more about evil than that; if they pretend otherwise, they are lying..."

Baldwin's attempt to bring Malcolm X's story to the big screen is also fascinating. In 1968, producer Marvin Worth hired Baldwin to write a script for a movie about Malcom. Baldwin moved to Los Angeles to work on the project, but it didn't go smoothly. From what I've read, his first treatment was more like a 200-page novel than a screenplay. It seems Baldwin's working habits were a bit chaotic, and his lifestyle in LA was quite expensive. As Baldwin struggled with the script, Worth brought in another writer, Arnold Perl, to help. However, the studio wasn't satisfied with the result, and Baldwin eventually quit the project.

What's intriguing is that the story doesn't end there. Baldwin and Perl reworked the manuscript and turned it into a documentary that was quickly "buried" because it was thought to be too inflammatory. Years later, that version of the script found its way to Spike Lee, who used it as a basis for his 1992 film 'Malcolm X'. Interestingly, Baldwin's estate kept his name out of the on-screen credits.

Baldwin's writing process fascinates me too. Despite having a typewriter (you have to be a person of a certain age to know what a typewriter is), he preferred to write in longhand on a legal pad. "You achieve shorter declarative sentences," he once said. He aimed to "write a sentence as clean as a bone," often overwriting in his first drafts and then cleaning them up in the editing process. I wonder how this approach influenced his work on the Malcolm X screenplay, and how it might have contributed to the challenges he faced in adapting his novelistic style to the demands of screenwriting

I was thrilled to learn that in 2017, the New York Public Library's Schomburg Centre for Research in Black Culture acquired a copy of one of Baldwin's scripts, written in his characteristic longhand. The library now has three of Baldwin's solo manuscripts for the project as well as the Baldwin-Perl screenplay. It's wonderful to think that these pieces of Baldwin's work, even though they didn't make it to the screen as he intended, have been preserved for future generations to study.

The more I learn about Baldwin, the more I appreciate the depth and breadth of his work and experiences. From his early days as a preacher to his time as an expatriate in France, from his novels to his film critiques and screenwriting attempts, Baldwin's life and work continue to offer rich insights into the human condition. His struggle with the Malcolm X project, in particular, highlights the complexities he faced in trying to bring important stories to a wider audience.

I find myself grateful for the profound influence that Jimmy Baldwin has had on my thinking and my life, and I'm sure I'm not alone in this sentiment. Baldwin's journey - as a writer, a critic, and a voice for change continues to inspire and challenge me, even a century after his birth.

The greatest tragedy is that the people who need his words most of all don’t read them and don’t know of the man, because they are ensnared in the Tic-Toc/Instagram world of influencers.

💜