This is Part 1 of a two-part series on resource inequality. Today: how colonial systems engineered extraction and institutional weakness. Next week: why resource curse language prevents real solutions and what breaking the colonial curse actually requires.

Introduction

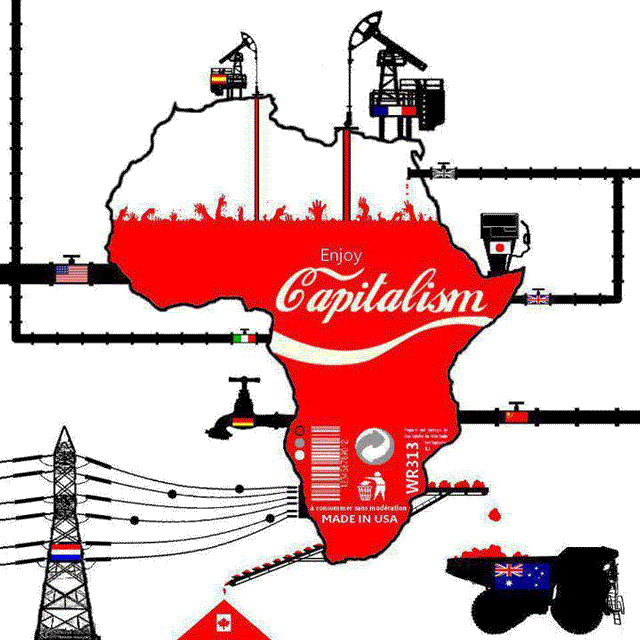

The prevailing narrative around natural resource wealth and inequality centres on what economists call the "resource curse,” the paradoxical tendency for resource-rich countries to experience greater inequality and slower development than their resource-poor counterparts. However, this framing fundamentally misdiagnoses the problem. The issue is not that natural resources are inherently problematic, but rather that the extractive systems governing them were deliberately engineered through colonialism to channel wealth upward and outward. What we call the resource curse is more accurately understood as the colonial curse, the lasting institutional legacy of systems designed for extraction rather than development.

The Mechanics of Extractive Inequality

Extractive industries drive inequality through several interconnected mechanisms that create what development scholars recognise as enclave economies. These operations typically feature high barriers to entry and capital-intensive production that favours large multinational corporations while generating relatively few local jobs. The resulting economic structure concentrates profits among a small elite while leaving host communities to bear environmental costs and economic volatility.

The phenomenon of "Dutch Disease" (a variant of the resource curse) exemplifies these distortions: commodity revenue surges appreciate the real exchange rate, undermining manufacturing and agriculture while deepening regional disparities. Meanwhile, volatile commodity prices create boom-and-bust cycles that make social spending unpredictable and erode long-term development planning. Most importantly, the concentration of resource rents invites elite capture and corruption, weakening governance and siphoning public funds away from health, education, and infrastructure investments that might otherwise reduce inequality.

Communities hosting extraction sites face a particularly cruel irony. they often experience the greatest environmental harms and social dislocation while seeing the least benefit from resource wealth. This pattern of environmental injustice compounds existing socio-economic marginalisation, creating deeper inequalities rather than the prosperity that resource wealth should theoretically enable.

Australia as the Exception That Proves the Rule

Australia stands as a notable outlier in this global pattern, and its success illuminates why the resource curse narrative misses the mark. Australia effectively manages its resource wealth through robust institutions and transparency mechanisms, including well-enforced procurement rules, open contracting, and parliamentary oversight that limit corruption and ensure revenues enter the public purse. The country has established sophisticated fiscal frameworks, including sovereign wealth funds like the Future Fund that smooth out commodity price shocks and ring-fence resource income for long-term investment.

Importantly, Australia's progressive taxation system, universal healthcare, and comprehensive social transfers redistribute wealth effectively, keeping inequality comparatively low. The country has also emphasised forward and backward linkages through local content requirements, research and development investments, and skills development programmes that integrate mining into the broader economy rather than allowing it to remain an isolated enclave.

The key insight is that Australia had these strong democratic institutions, rule of law, and diversified economy before its mining boom. This institutional foundation was not accidental; it reflects Australia's history as a settler colony where European powers invested in building durable institutions meant to serve a permanent population.

The Colonial Blueprint: Engineering Extraction

This institutional difference reveals the true source of resource-related inequality: the colonial legacy that shaped how different territories were incorporated into the global economy. European colonial powers did not establish colonies to create prosperous, equitable modern states. They designed them for extraction, creating what can be understood as extractive institutions by design. The institutions established during colonialism; legal systems, administrative borders, security forces, served primarily to maintain control over populations and facilitate resource removal for the benefit of colonial metropoles. This process often deliberately dismantled complex existing governance and economic systems, replacing them with simplified, top-down structures focused on extraction rather than broad-based development.

Critically, there was no investment in building the foundations of diversified economies: mass education, infrastructure for internal trade, industrial development, or civil society institutions capable of holding power accountable. This created massive structural deficits that persisted long after formal independence.

The Post-Colonial Trap: Neocolonialism and Institutional Weakness

When colonies gained independence, they inherited these fundamentally flawed, extractive institutions. The challenge wasn't simply that institutions were "new," they were designed for an entirely different purpose and remained embedded in global systems that continued to disadvantage former colonies through various neocolonial mechanisms.

Newly independent nations, often cash-strapped and lacking technical expertise, found themselves negotiating with sophisticated multinational corporations possessing far superior resources, legal teams, and market information. This power imbalance typically resulted in contracts heavily favouring corporations while depriving host countries of fair shares of resource rents.

The competitive dynamics between developing nations further exacerbated this problem, creating a "race to the bottom" as countries offered ever-lower tax rates, royalty fees, and environmental regulations to attract foreign investment. This dynamic reflects the weak economic position these nations inherited from the colonial hierarchy rather than any natural market outcome.

Perhaps most tragically, the small elites who inherited state power often simply stepped into the extractive role previously played by colonial administrators. Using state resource wealth to enrich themselves and their patronage networks rather than pursuing national development, these elites perpetuated the colonial model with only a change in personnel.

The situation was often worsened by debt crises that led to International Monetary Fund and World Bank Structural Adjustment Programmes. These programmes frequently required cuts to public spending, privatisation of state assets, and economic deregulation that further weakened already fragile social safety nets and entrenched poverty and inequality.

Settler vs. Extractive Colonialism: A Tale of Two Legacies

The contrast between Australia and countries like the Democratic Republic of Congo illustrates how different colonial models produced vastly different institutional legacies. Australia was established as a settler colony where the goal was creating a permanent European society. This required building durable institutions, courts, banks, schools, legislatures, meant to serve a citizenry over the long term.

Congo, by contrast, exemplified extractive colonialism at its most brutal. Under King Leopold II and later Belgium, the territory was administered purely for rubber and ivory extraction with unimaginable violence and zero investment in Congolese institutional development. At independence in 1960, there were almost no university graduates, lawyers, or engineers among the Congolese population. The state they inherited was a hollow shell designed only for extraction, setting the stage for decades of dictatorship and conflict over mineral wealth.

The contrast between Australia's resource-driven prosperity and Congo's resource-fuelled tragedy reveals that geology is not destiny - history is. But understanding how colonial systems engineered extraction and institutional weakness is only half the story. The more challenging question remains; if the problem is not cursed resources but colonial institutions and their neocolonial successors, how do we actually break free from systems that were designed to be self-perpetuating?

In Part 2, I will examine why simply calling this a resource curse actively prevents real solutions, explore what breaking the colonial curse would actually require, and confront the uncomfortable truth about why there are no technocratic shortcuts to the kind of fundamental political change that true resource justice demands.

The recent débàcle resulting from significant petroleum exploration and subsequent production in the waters off the coast of Guyana presents a classic, modern case in point. Previously, the governments of Guyana had taken a noble stance to protect its super-rich Amazon rainforest from plunder by overseas interests. The contrast in the allocation of long-term extraction concessions to multi-national enterprises is astounding. Whither the 'Poor and the Powerless' Guyanese masses, Indian, African and Indigenous?

I've run this piece through 2 different AI detectors (Quillbot, GPTZero). Both are fairly sure the piece (75%) was generated by an AI LLM. Are you contributing original, thought-provoking work, or are you using a shortcut to produce a textual collage of other writers' work and eventually profit from it?