How international capital flows bypass democratic control and reshape urban landscapes

Picture this: A luxury flat in central London sits empty for eleven months of the year. Its owner, listed as a company registered in the British Virgin Islands, has never set foot in the property. The building's planning permission was fast-tracked through a local authority desperate for investment, whilst long-term residents watch their community transform around them, unable to afford the rising rents that follow such developments.

This isn't just a story about gentrification or housing inequality, it's about something more fundamental: the operation global wealth chains. These are the complex networks through which capital flows across borders, often invisibly, to reshape our cities in ways that local communities have little power to influence or resist.

What Are Global Wealth Chains?

Global wealth chains are the financial equivalent of global supply chains. Just as your smartphone contains components manufactured across multiple countries before reaching your hands, today's urban property investments often involve capital assembled from multiple jurisdictions, channelled through layers of legal structures, before landing in your neighbourhood.

These chains typically involve:

Wealth holders seeking to park capital offshore

Financial intermediaries (private banks, wealth managers, family offices)

Legal structures (shell companies, trusts, partnerships)

Offshore jurisdictions offering secrecy and tax advantages

Investment vehicles targeting urban property markets

Local facilitators (estate agents, planning consultants, developers)

The result is a system where someone in Singapore can own property in Manchester through a company registered in Delaware, managed by a trust in Jersey, with financing arranged through Luxembourg, all whilst remaining essentially invisible to local authorities and communities.

One Hyde Park

The London Laboratory

London provides perhaps the clearest example of how global wealth chains operate in practice. Research by Transparency International found that £4.4 billion worth of London property has been bought with suspicious wealth over the past three decades. But this figure only captures the most obvious cases, the true scale is likely far larger. In 2023 research that I carried out with colleagues we found there were 138,000 such properties in England and Wales, 95,000 were located in London, each costing on average £1,300,000.

Take the case of One Hyde Park, one of London's most expensive residential developments. Of the 86 apartments sold by 2014, at least 17 were owned through offshore companies, with beneficial ownership often impossible to trace. These weren't just investments. they were endpoints in complex and opaque global wealth chains that stretched across multiple continents and legal jurisdictions.

The development process itself reveals how these chains operate:

Land acquisition: Often involving companies registered in low-transparency jurisdictions (these are often tax havens, but they also include some onshore jurisdictions like Delaware in the USA, Luxembourg, Switzerland and Liechtenstein to name but a few in Europe).

Development financing: Structured through multiple entities to minimise tax exposure.

Marketing and sales: Targeted at international wealth managers and family offices (A family office is a private wealth management firm that provides financial, investment, and estate planning services exclusively for an ultra-high-net-worth family, ensuring their wealth is preserved and managed across generations).

Ongoing ownership: Maintained through offshore structures that preserve anonymity

Beyond London: A Global Phenomenon

Whilst London is often cited as the poster child for this phenomenon, global wealth chains operate in cities worldwide. In New York, the Time Warner Centre became notorious for its concentration of shell company ownership. In Vancouver, offshore ownership became so prevalent that the city introduced an empty homes tax specifically targeting overseas investors.

What's striking is how similar patterns emerge across different contexts:

Miami's luxury condo market attracting Latin American wealth

Sydney's harbour-front properties drawing Asian capital

Berlin's gentrifying neighbourhoods experiencing waves of international investment

Dublin's property boom fuelled partly by global funds seeking European exposure

Each city becomes a node in overlapping global wealth chains, with local property markets increasingly detached from local economic conditions.

The Democratic Deficit

The operation of global wealth chains creates what is termed a democratic deficit in urban governance. Local authorities find themselves making planning decisions about developments that will primarily serve global capital flows rather than local housing needs.

Consider the planning permission process. In theory, this is where local communities can influence development. In practice, when developments are funded through global wealth chains, the economic and political pressures often overwhelm local concerns:

Economic dependence: Local authorities become dependent on development fees and business rates from international investment

Expertise gaps: Planning committees lack the resources to understand complex international ownership structures

Regulatory arbitrage: Developers can threaten to relocate investment if faced with unwelcome regulation

Time horizons: Global capital can wait out local political cycles

The result is "regulatory capture by capital mobility", where the mere possibility of capital flight shapes local decision-making.

The Human Cost

Behind these abstract financial flows are real human consequences. Global wealth chains don't just move money, they displace people, communities, and ways of life.

My research has found that in Kensington and Chelsea, the London borough with the highest concentration of offshore-owned property, there is also some of the most acute housing inequality in the UK. The Grenfell Tower tragedy occurred in this same borough, highlighting a dastardly contrast between global wealth and local deprivation.

This isn't coincidental. Global wealth chains contribute to what urban geographer Neil Smith called the "rent gap", the difference between current rents and potential rents if properties were "improved" for higher-income users. International capital, seeking maximum returns, naturally gravitates towards areas where this gap is largest, again displacing existing communities in the process.

Resistance and Regulation

The invisibility of global wealth chains makes them particularly difficult to regulate, but some cities are fighting back:

Vancouver introduced a foreign buyer's tax and empty homes tax, though enforcement remains challenging when ownership structures are opaque.

New York passed the Corporate Transparency Act, requiring disclosure of beneficial ownership for certain property purchases, though the threshold is set high enough that many transactions escape scrutiny.

London has been slower to act, though the Economic Crime Act 2022 finally introduced a register of overseas entities owning UK property, a measure campaigners had been demanding for over a decade.

But perhaps the most interesting resistance comes from community organising. Groups like the Focus E15 Mothers in East London have developed sophisticated analyses of how global investment patterns affect local housing, whilst Transparency International has pioneered techniques for tracing beneficial ownership through complex corporate structures.

Reading the Chains

Understanding global wealth chains requires "forensic geography", the ability to trace how global financial flows translate into local spatial transformations. This involves:

Following the money: Tracing ownership through corporate records and property registries. A process easier said, than done!

Mapping the networks: Understanding how different actors (banks, lawyers, developers) connect across jurisdictions.

Timing the flows: Recognising how global economic cycles drive local property booms.

Reading the landscape: Seeing how global capital literally reshapes urban space.

I don’t think what my colleagues and I have been doing is just an academic exercise. Communities fighting displacement need to understand these dynamics to develop effective resistance strategies. Local authorities need this knowledge to design effective policies. And citizens need to recognise how global processes shape their local experiences.

Beyond Transparency: Structural Change

Whilst transparency measures are important, they're not sufficient. Global wealth chains exist because they serve the interests of those who control large amounts of capital. Simply making them visible doesn't change their fundamental logic.

More radical approaches might include:

Community land trusts that remove land from speculative markets

Social housing programs that compete directly with private investment

Financial transaction taxes that make speculative investment less profitable

Democratic planning processes that give communities genuine power over development

The goal isn't to stop all international investment, but to ensure that global capital flows serve local needs rather than displacing them.

The Bigger Picture

Global wealth chains in urban property markets are part of a broader transformation in how capitalism operates in the 21st century. As Thomas Piketty observed, we're living in an era where returns to capital increasingly exceed economic growth rates, driving wealth concentration and asset price inflation.

Urban property has become a key vehicle for this process, not just because cities are where economic growth is concentrated, but because property offers a way to store wealth that's relatively secure and often appreciating. Global wealth chains are the infrastructure that makes this possible on a planetary scale.

Understanding these dynamics is critical for anyone concerned about urban inequality, democratic governance, or social justice. They help explain why housing has become unaffordable in so many cities, why local communities often feel powerless in the face of development, and why traditional approaches to urban planning are increasingly inadequate.

But understanding is just the first step. The real challenge is building the political movements and institutional changes needed to ensure that our cities serve their residents rather than distant wealth holders.

Further Reading:

Rowland Atkinson, “Alpha City”

Oliver Bullough, "Moneyland: Why Thieves and Crooks Now Rule the World and How to Take It Back"

Transparency International UK, "Hiding in Plain Sight" reports

Anna Minton, "Big Capital: Who is London For?"

My Published work (with co-authors) on Global Wealth Chains includes:

Anchoring capital in place: The grounded impact of international wealth chains on housing markets in London https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0042098019839875

What’s in the laundromat? Mapping and characterising offshore-owned residential property in London https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/23998083231155483?af=R&ai=1gvoi&mi=3ricys

Applying the global wealth chain typology to property purchases in the Liverpool and Merseyside Area https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0308518X231191934

TfL Report: Tax Haven Money in London’s Property https://www.academia.edu/104816496/TfL_Report_Tax_Haven_Money_in_London_s_Property

My own book - Hypercapitalism, Global Wealth Chains and the Struggle for the Right to the City: How Finance Reshapes Our Urban Futures (Palgrave Macmillan) – is to be published in 2026

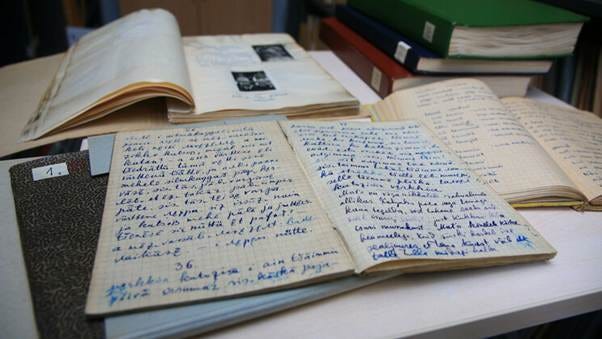

This is all so real, and so devastating. Aside from the economic actions and markers of how this has occurred, I am floored with sadness thinking about the cultural implications. The other night I was reading some pieces of writing I have somewhere which are basically transcriptions of childhood memories my parents have relayed onto me. I am from Ecuador, specifically Quito, and my parents are both boomers who lived in that city their entire lives. Their memories mapped the city out to me, tiny back then compared to the sprawling hell it’s becoming. They speak of the businesses that existed in the center of social and commercial life all those decades ago: “this family made excellent suits so all the politicians would go there for tailoring”, “that person ran a magazine and comic book store that brought media in from everywhere”, etc. This doesn’t exist anymore, and I feel desperately sad. Now like everywhere, people will go to some opulent mall to a foreign-owned store to get a mass produced item of low quality that nobody feels proud of having made. And us? We don’t know each other anymore, and we think less of things that aren’t foreign. Colonization, subsequent foreign intervention and global capitalism have taken our means, raptured our identity, and diluted our culture which was already riddled with self-hatred since our subjugation from the colonizer. We did it all wrong.

The clarity provided on this vital area of Global Wealth Chains and The Invisible Networks Reshaping Our Cities was very much appreciated as were the examples of resistance to this insidious activity and examples of further reading. All in all a both stimulating and enlightening read.