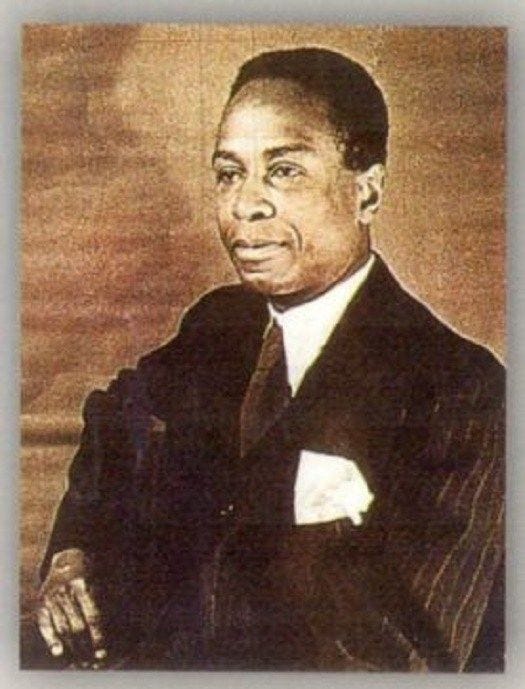

Early Life and Political Development

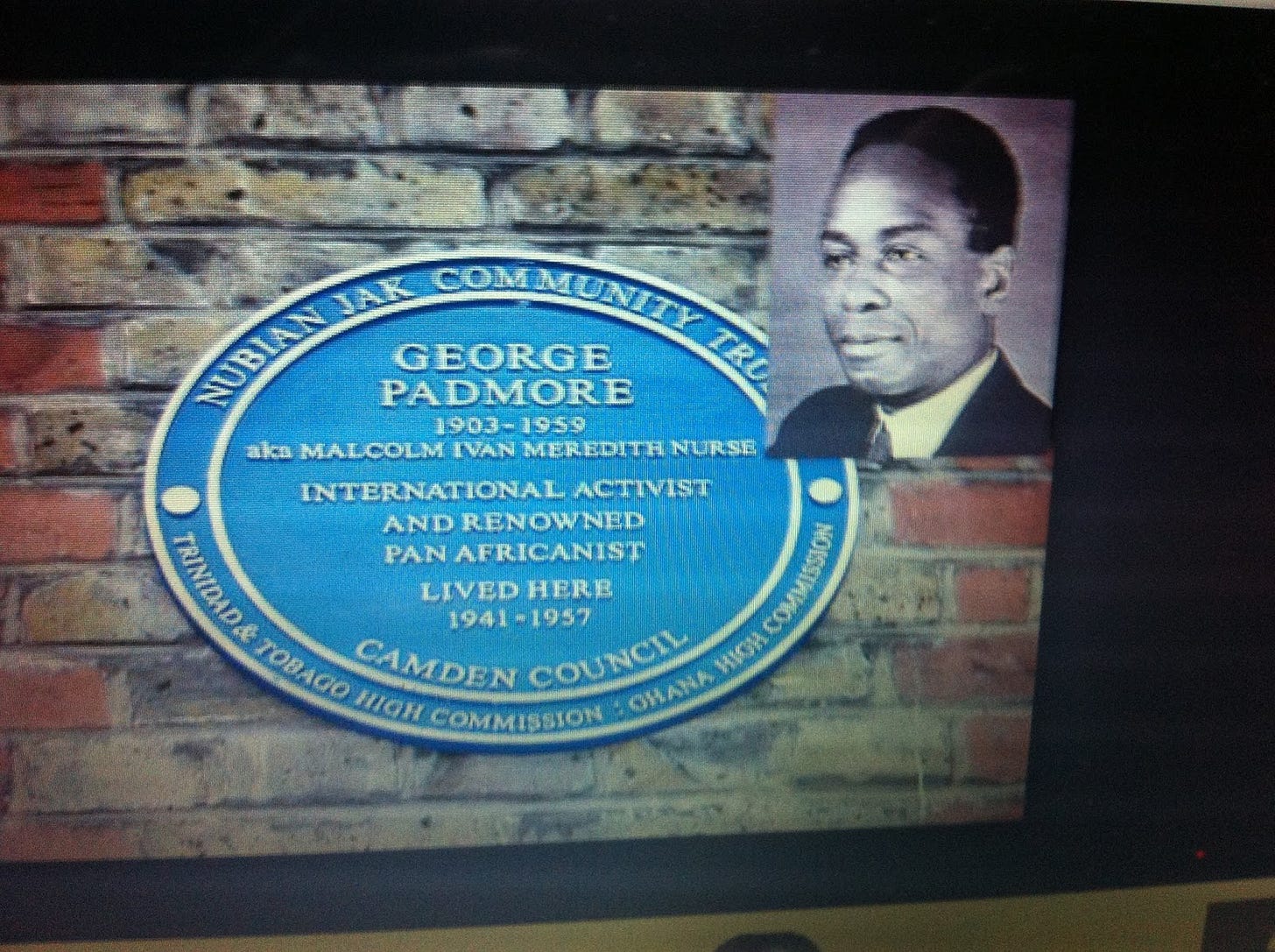

Born Malcolm Ivan Meredith Nurse in Trinidad in 1903, George Padmore emerged as one of the most significant intellectuals and activists in the Pan-African movement of the 20th century. His life's work spanned journalism, political organisation, and advisory roles that profoundly shaped anti-imperialist thought and the independence movements across Africa.

Padmore initially travelled to the United States to study medicine, but his path soon changed as he became deeply involved with Communist Party activities. His political awakening led him to focus intensely on African independence movements and anti-colonial struggles. However, the 1930s marked a turning point in his ideological journey, as he broke ties with the Communist Party due to fundamental differences in priorities.

The Soviet Union had begun emphasising alliances with colonial powers like Britain and France, categorising them as "democratic-imperialisms" in contrast to "fascist-imperialist" powers such as Germany and Japan. Padmore found this position incompatible with his unwavering commitment to African liberation. He viewed the Soviet shift as a betrayal of colonised peoples, whose freedom he believed should not be subordinated to European geopolitical considerations. Additionally, he was dissatisfied with the Communist Party's insufficient attention to racial inequality, which he considered central to the struggle against imperialism.

London Years and Literary Contributions

In 1934, Padmore settled in London, which became his base for intellectual and organisational work. The British capital provided a meeting ground where he collaborated with other Pan-Africanist thinkers and activists from across Africa and its diaspora. During this period, he produced some of his most influential writings.

His 1936 book How Britain Rules Africa offered a searing critique of British colonial policies and highlighted the systematic exploitation of African resources and peoples. This work became essential reading in anti-colonial circles. Later, in Pan-Africanism or Communism? (1956), Padmore examined the ideological choices facing newly independent African nations, advocating for Pan-Africanism as the most authentic path to true liberation and unity.

Throughout his career, Padmore remained a prolific journalist, using his pen to raise awareness about colonial injustices and to garner international support for independence movements. His opposition to Italy's invasion of Ethiopia in 1935 exemplified his approach. He viewed this aggression against one of Africa's few independent nations as a pivotal moment in the global anti-imperialist struggle, organising protests and campaigns to defend Ethiopian sovereignty.

Collaborative Relationships

Padmore's effectiveness stemmed partly from his ability to build meaningful connections with other leading figures in the liberation movements. His relationship with Kwame Nkrumah proved particularly consequential for African history. Their first meeting occurred in London in 1945, when Nkrumah, fresh from the United States, was introduced to Padmore by C.L.R. James, another towering Pan-Africanist intellectual.

Padmore became both mentor and collaborator to Nkrumah, guiding him in both theoretical understanding and practical organising. Their partnership deepened when Nkrumah returned to Ghana (then Gold Coast) to lead the independence movement. Following Ghana's independence in 1957, Padmore moved there to serve as Nkrumah's advisor on African affairs, helping to shape policies that advanced Pan-African unity. Their joint efforts culminated in the All-African Peoples' Conference in Accra in 1958, which brought together liberation movements from across the continent. This groundwork later influenced the formation of the Organisation of African Unity in 1963.

Padmore’s relationship with Kwame Nkrumah extended beyond public solidarity into the realm of private strategy. Their correspondence (much of which occurred during the 1940s and 1950s) reveals the depth of Padmore’s influence on Ghana’s emerging role in Pan-African affairs. Scholars such as Marika Sherwood have shown that Padmore advised Nkrumah not only on ideological matters but also on diplomatic appointments, regional alliances, and conference logistics. These letters demonstrate how Padmore functioned as a transnational strategist - neither fully insider nor outsider, but a diasporic intellect whose epistolary engagement helped engineer the architecture of postcolonial diplomacy.

Padmore also maintained important relationships with other significant figures in Black liberation movements. With W.E.B. Du Bois, he collaborated on organising the Fifth Pan-African Congress in Manchester in 1945, an event that historians recognise as a watershed moment in the anti-colonial struggle. While Du Bois brought intellectual gravitas and his status as an elder statesman of Pan-Africanism, Padmore contributed his organisational skills and his focus on practical strategies for independence.

His connection with Claudia Jones similarly reflected a shared commitment to anti-colonialism and socialism. Both had Communist Party backgrounds, and both worked tirelessly to highlight the struggles of African and Caribbean peoples. Jones's founding of the West Indian Gazette in London echoed Padmore's emphasis on using journalism to advance liberation causes.

Enduring Legacy

Padmore passed away in London in 1959, but his impact continues to resonate in contemporary discussions about African unity, global solidarity, and resistance to neo-colonial exploitation. His life demonstrates the power of intellectual activism in driving societal change.

The issues Padmore identified, economic exploitation, political fragmentation, and social inequality, remain relevant today. His vision of a unified Africa still guides organisations working toward continental collaboration. His emphasis on the interconnectedness of struggles against oppression speaks to our globalised world, where challenges such as racial injustice, economic inequality, and climate change require coordinated international responses.

Perhaps most importantly, Padmore stands as a model for how unwavering commitment to justice and equality can leave a lasting imprint on history. His work reminds us that the fight for these values transcends geographic boundaries and continues across generations. His legacy offers valuable lessons for addressing modern forms of colonialism and exploitation, proving that ideas conceived in the struggle against imperialism remain vital tools for contemporary activism and governance.

Analysis and Significance

This examination of George Padmore's life and work reveals several significant insights about anti-colonial movements, Pan-Africanism, and ongoing struggles for global justice.

Padmore's ideological evolution, from Communist Party activist to independent Pan-Africanist, illuminates the complex development of liberation ideologies throughout the 20th century. His principled break with communism underscores a fundamental tension between universalist political theories and the specific needs of colonised peoples. When Soviet policy shifted toward accommodating European colonial powers as allies against fascism, Padmore recognised this as an unacceptable compromise that subordinated African liberation to European geopolitical interests. This stance highlights how international movements sometimes failed to centre racial inequality in their analysis of imperialism.

The narrative demonstrates the transformative power of intellectual activism. Through his prolific writings and organisational efforts, Padmore wielded ideas as practical tools for political change. His books, particularly How Britain Rules Africa and Pan-Africanism or Communism? provided both analytical frameworks and moral arguments that equipped independence movements with intellectual ammunition. His journalism connected disparate struggles across continents, building awareness and solidarity that proved essential to anti-colonial resistance.

Padmore's extensive network of relationships with figures such as Kwame Nkrumah, W.E.B. Du Bois, and Claudia Jones, reveals the importance of transnational connections in liberation movements. These intellectual and political alliances created channels for the exchange of ideas, strategies, and moral support that accelerated independence movements across Africa and strengthened diaspora communities' involvement in these struggles. The Manchester Pan-African Congress of 1945, which Padmore helped organise, exemplifies how these networks could materialise into events with concrete historical impact.

The story of Padmore also highlights the distinctive role of the African diaspora in shaping continental politics. Operating primarily from London and bringing his Trinidadian perspective to bear on African issues, Padmore embodied the diasporic dimension of Pan-Africanism. His trajectory demonstrates how people of African descent outside the continent made vital intellectual and organisational contributions to independence movements within Africa itself.

Perhaps most significantly, Padmore's concerns about economic exploitation, political fragmentation, and social inequality remain strikingly relevant today. His critique anticipated the challenges of neo-colonialism, situations where formal independence might mask continued economic domination and resource extraction by former colonial powers. This prescience suggests that contemporary movements for global justice might find valuable strategies and insights in Padmore's analysis of how imperial power operates.

The continued resonance of Pan-Africanist ideas in discussions about African unity, development strategies, and international relations testifies to the enduring value of the intellectual tradition that Padmore helped to build. His vision of solidarity across racial and national lines, grounded in a clear-eyed analysis of power structures, continues to offer resources for addressing contemporary injustices. In this sense, examining Padmore's life does more than recover an important historical figure, it provides conceptual tools for understanding and confronting persistent forms of exploitation and inequality in our present moment.

It needs to be said that despite his pivotal role in shaping Ghana’s Pan-African diplomacy, Padmore’s final years were tinged with disillusionment. Disheartened by the creeping authoritarianism of Nkrumah’s regime and the slow pace of continental unity, he left Accra before his death and returned to London in 1959. His disappointment did not stem from cynicism, but from a principled belief that independence without transformation risked reproducing colonial hierarchies under new flags. His insight that true liberation required not just political independence but fundamental transformation of power structures was ahead of its time. The concept of neocolonialism wouldn't be widely articulated until the 1960s, but Padmore was already identifying its essential dynamics in the late 1950s.

Legacy

George Padmore's intellectual legacy offers essential tools for understanding how power adapts and persists across political changes. Recovering his insights from historical obscurity isn't merely an act of scholarly justice - it's a strategic necessity for anyone serious about dismantling, rather than simply rebranding, structures of exploitation and domination.

References

Padmore, G., 1969. How Britain rules Africa. New York: Negro Universities Press. (Originally published 1936)

Padmore, G., 1972. Pan-Africanism or Communism? The coming struggle for Africa. Garden City, NY: Doubleday Anchor. (Originally published 1956)

Sherwood, M., 2012. Pan-Africanism and communism: The Communist International, Africa and the diaspora, 1919–1939. Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press.

Great reference documents Rex