Garvey’s “Philosophy and Opinions”, Appiah's "In My Father's House” and Rodney’s “How Europe Underdeveloped Africa”

Comparison and contrast

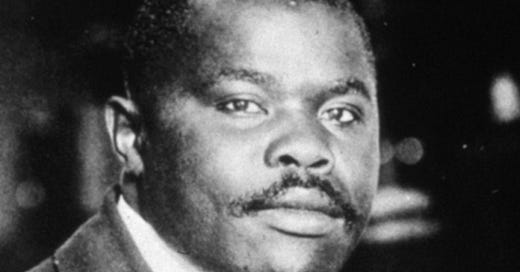

This Liberation Letter is my attempt at comparing and contrasting the ideas of three influential thinkers on the subject of African identity, culture, and development: Marcus Garvey, Kwame Anthony Appiah, and Walter Rodney. While all three are influential, Garvey and Rodney are far more well known among the masses of Black people. Appiah's influence, in contrast, is largely confined to the Academy. In my thinking this is not a trivial distinction, to the contrary it is very important because it reflects the different ways these thinkers' ideas have been disseminated and adopted. Garvey's and Rodney's more direct, action-oriented approaches likely contributed to their wider popular influence, while Appiah's more philosophical and academic work has found its primary audience in scholarly circles.

The comparison is undertaken through my interpretation of the main books authored by these thinkers, Garvey’s Philosophy and Opinions, Volume 1 (published in 1977), Appiah’s, In My Father’s House (1992) and Walter Rodney’s How Europe Underdeveloped Africa (first published in 1972). My appraisals don’t proceed in chronological order for reasons that will become apparent to the reader by the end of this Letter.

Philosophy and Opinions of Marcus Garvey Volume 1

In the book Garvey outlines a vision for Black empowerment and liberation. He emphasises the importance of racial pride and self-reliance and he promotes the beauty and value of Black culture and heritage, urging people of African descent to embrace their identity with confidence. “If you have no confidence in yourselves, you are twice defeated in the race of life” is a memorable exhortation in the book. Central to Garvey's philosophy is Pan-Africanism, advocating for worldwide Black unity and economic independence as vital for true liberation.

Garvey strongly encourages the establishment and support of Black-owned businesses and economic institutions. Perhaps his most controversial proposal is the idea of repatriation to Africa. He viewed the continent as the true homeland for people of African descent and suggests a return as a path to genuine freedom. This notion aligns with his broader critique of white supremacy and the racist ideologies prevalent in early 20th century America and European colonialism. Garvey's work also promotes Black nationalism, arguing that separate Black nation-states are necessary for achieving true equality and self-determination. Alongside this political vision, he stresses the significance of education and cultural development in uplifting the Black community.

In My Father's House: Africa in the Philosophy of Culture

This work by Kwame Anthony Appiah is a non-fiction work composed of interconnected essays that explore various aspects of African identity, culture, and philosophy. While there isn't a traditional plot, the book does have a structure and progression of ideas.

Kwame Anthony Appiah's "In My Father's House" offers an exploration of African identity, culture, and philosophy. The book opens with Appiah's personal musings on his Ghanaian heritage and his upbringing in a multicultural milieu, setting the stage for a nuanced examination of African identity. From this personal foundation, Appiah proceeds to investigate the very concept of Africa. He questions the notion of a monolithic African identity and culture, encouraging readers to consider the diversity and complexity within the continent. The greater part of the book examines the impact of colonialism on African thought and cultural expression, detailing how colonial experiences have moulded contemporary African identities and highlighting the lasting effects of this historical period. Appiah offers a critical assessment of Pan-Africanism, tracing its roots, examining its influence, and discussing its potential shortcomings. This leads to a broader discourse on race and ethnicity, where Appiah challenges oversimplified racial categorisations and explores the intricate processes of their construction and perpetuation.

Language plays a central role in Appiah's analysis of African identities and cultures. He pays particular attention to its significance in post-colonial nations, where linguistic choices often carry weighty cultural and political implications. The book also ventures into the realm of philosophy, exploring the intricate relationship between African traditional beliefs and Western philosophical traditions. This exploration extends to an examination of "nativism" in African thought, probing its implications for cultural authenticity.

Appiah does not shy away from contemporary issues, addressing the challenges that modernisation and globalisation pose to African cultures and identities. He considers how these forces shape and reshape African experiences in an increasingly interconnected world. The book concludes with Appiah's reflections on the future of African philosophy and cultural studies. He offers insights into potential directions for these fields, encouraging continued dialogue and exploration of African identities in all their complexity.

Throughout the book, Appiah weaves together personal anecdotes, historical analysis, and philosophical arguments to present a multifaceted view of African culture and identity. His work challenges readers to move beyond essentialist views of African culture and embrace a more fluid and dynamic understanding of identity.

Garvey and Appiah

Marcus Mosiah Garvey was born in 1887, he died in 1940 and as I have said Appiah’s book was first published in 1992. They are separated by nearly a century and this I believe explains their distinct approaches to understanding and addressing African and Black identity in a world shaped by colonialism and its aftermath.

Garvey's ideas, rooted in the early 20th century context of entrenched racial oppression, focused on racial pride, economic independence, and the unity of Black people worldwide. His approach was decidedly practical and action-oriented, aimed at immediate and tangible improvements in the lives of Black people through economic self-reliance and political independence. In contrast, Appiah's work emerges from a late 20th century, postcolonial context, offering a more nuanced and philosophically complex view of African identity. Where Garvey saw strength in racial unity and separation, Appiah questions the very notion of a monolithic African identity. His cultural analysis challenges essentialist views of race and culture, exploring instead the hybrid and often contradictory nature of African identities.

Appiah's approach is more academic, engaging with philosophical concepts and postcolonial theory. He critically examines ideas that Garvey held dear, such as Pan-Africanism, highlighting their limitations and contradictions. Rather than advocating for a 'pure' African identity, Appiah embraces the diverse influences that have shaped African cultures, including those stemming from the colonial experience.

This contrast between Garvey and Appiah reflects broader debates within African and Black intellectual traditions about how to understand identity, confront racism and colonialism, and chart a path forward for African peoples. Garvey's emphasis on racial empowerment and unity, while powerful in its time, can be seen as somewhat simplistic when viewed through the lens of Appiah's more complex cultural analysis.

Yet, it's important to understand both perspectives within their historical contexts. Garvey's ideas emerged in a time of overt racial oppression and limited opportunities for Black advancement, making his call for unity and self-reliance particularly resonant. Appiah, writing in a post-independence era marked by globalisation and shifting notions of identity, had the luxury of a more nuanced approach. The tension between Garvey's call for unity based on shared heritage and Appiah's exploration of diversity within African identities continues to inform discussions about race, culture, and identity in the African diaspora and beyond.

The evolution from Garvey's more essentialist view to Appiah's questioning of fixed identities mirrors broader shifts in how we understand race and culture. It reminds us of the complex interrelationship between political action and philosophical reflection in addressing issues of identity and empowerment. As we continue to engage with questions of race and identity in the 21st century, the contrasting approaches of thinkers like Garvey and Appiah provide valuable perspectives, challenging us to consider both the power of unity and the richness of diversity in African and Black experiences.

How Europe Underdeveloped Africa

Walter Rodney, a Guyanese historian and political activist, approached African issues from a decidedly Marxist perspective. His seminal work, "How Europe Underdeveloped Africa", published in 1972, provides a materialist analysis of African history and development. In essence, materialist analysis, as used by Rodney, views economic structures and relationships as the fundamental forces shaping society, history, and development. It prioritises the study of how material conditions and economic interactions influence all aspects of human life, including social, political, and cultural systems. This approach allows Rodney to argue that Africa's underdevelopment was not innate, but a direct result of its economic relationship with Europe, particularly through colonialism and exploitation.

In the book, Rodney challenges prevailing narratives about Africa's past and present, presenting a compelling argument about the continent's relationship with Europe. He begins by dismantling the notion that pre-colonial Africa was primitive or undeveloped. He paints a vivid picture of diverse and sophisticated societies that flourished across the continent before European intervention. This sets the stage for his examination of how external forces disrupted Africa's autonomous development.

The Atlantic slave trade serves as Rodney's starting point for exploring European exploitation of Africa. He meticulously documents how slavery not only caused immense human suffering but also severely disrupted African societies and economies. This disruption, Rodney argues, laid the groundwork for subsequent forms of exploitation. Moving into the colonial era, Rodney provides a detailed account of how European powers systematically extracted resources and labour from Africa. He argues that this exploitation was not merely incidental but fundamental to Europe's own development, creating a relationship of dependency that stunted Africa's economic growth. His analysis extends beyond economic structures to examine the cultural and educational impositions of colonialism. He explores how colonial education systems and cultural pressures reinforced European dominance and African dependency, shaping mindsets and societal structures in ways that outlasted formal colonial rule.

Throughout the book, Rodney draws insightful comparisons between Africa's developmental trajectory and those of Europe and other parts of the world. These comparisons serve to highlight the role of exploitation in European advancement and to challenge Eurocentric narratives of progress and civilisation.

Importantly, Rodney's work doesn't end with independence movements. He extends his analysis into the post-colonial era, arguing that many of the exploitative economic relationships established during colonialism continued in new forms, a phenomenon he identifies as neo-colonialism.

While Rodney's focus is primarily on European actions and their consequences, he also discusses African agency. He explores the complexities of African participation in these historical processes, including various forms of resistance and collaboration. Importantly, he places Africa's underdevelopment in the broader context of global capitalism and imperialism, offering a nuanced understanding of how local and global forces interacted to shape the continent's history.

The book concludes with a call for radical change in Africa's economic and political structures. Rodney argues that overcoming the legacy of underdevelopment requires a fundamental restructuring of Africa's relationship with the global economic system.

Garvey, Appiah and Rodney

The main differences between Appiah and Garvey on one hand, and Walter Rodney on the other, lie in their fundamental approaches to understanding African identity, development, and liberation. This comparison reveals significant divergences in their analyses of African societies and their prescriptions for change. I can think of at least six points of divergence:

1. Rodney emphasises class struggle as the primary lens through which to understand African societies and their relationship to global capitalism. He sees African underdevelopment as a direct result of European exploitation, arguing that Europe actively underdeveloped Africa through slavery, colonialism, and neo-colonialism. This class-based analysis stands in stark contrast to both Garvey's focus on racial unity and Appiah's cultural explorations.

2. Rodney's work is deeply rooted in economic analysis. He examines how the integration of Africa into the global capitalist system led to the distortion of African economies and social structures. This economic focus is largely absent from Garvey's racial empowerment narrative and receives limited attention in Appiah's cultural analysis.

3. Rodney views liberation as requiring both class struggle within Africa and resistance to external imperialism. This dual focus on internal class dynamics and external economic relationships is more comprehensive than Garvey's emphasis on racial solidarity or Appiah's exploration of cultural identities.

4. Rodney's approach is more explicitly political and revolutionary. He argues for the necessity of socialist transformation in Africa as a means of overcoming underdevelopment. This stands in contrast to Garvey's focus on racial self-reliance and Appiah's more academic exploration of cultural dynamics.

5. While Garvey promoted a form of Pan-Africanism based on racial unity, and Appiah critiqued Pan-Africanism from a cultural perspective, Rodney advocated for a class-based Pan-Africanism. He saw the unity of African working classes as crucial for challenging both internal exploitation and external imperialism.

6. Rodney's analysis is more historically grounded, tracing the development of African societies from pre-colonial times through the colonial era and into the post-independence period. This historical materialism provides a depth of context that is less evident in Garvey's more immediate calls for action or Appiah's contemporary cultural analysis.

In essence, where Garvey emphasises racial empowerment and unity, Appiah explores the complexities of cultural identity, and Rodney focuses on class struggle and economic transformation. In my view, Rodney's approach provides a more systemic critique of global capitalism and its impact on Africa, arguing that true liberation requires fundamental changes in economic structures both within Africa and globally.

This comparison highlights the diverse strands of thought within African and Black intellectual traditions. It underscores the ongoing debates about the relative importance of race, culture, and class in understanding and addressing the challenges faced by African societies. Rodney's class-based approach offers a different perspective from both Garvey's racial unity and Appiah's cultural analysis, emphasising the need to consider economic structures and global power dynamics in any comprehensive understanding of African realities.

In the early 21st Century I tilt towards Rodney and would argue that Garvey and Appiah’s focus on identity politics, so central to much of their analyses, distracts from more fundamental economic conflicts and class struggles. This view aligns with the perspective that identity is "neoliberalism's baby that obscures the more basic conflict in all societies". I would further argue that by neglecting the material conditions and economic structures that shape society, Appiah's cultural analysis, much like Garvey's earlier focus on racial unity, falls short of offering a complete picture of the challenges facing African societies. A more holistic understanding would need to incorporate the economic analyses of thinkers like Rodney, balancing cultural insights with a robust examination of class structures and global economic systems.

I hope that by now, readers would be aware as to why this contrast and comparison of three thinkers and their writings was not presented in chronological order.