Introduction

In the last newsletter, I examined how the Peterloo Massacre of 1819 and the transportation of the Tolpuddle Martyrs in 1834 represented pivotal moments in British history when ordinary people faced violent opposition while demanding basic rights. And as stated in that newsletter these events were not isolated incidents but part of a global pattern where the powerless must organise and resist to gain recognition under systems designed to exclude them.

Today, I turn to two significant South African events - the Sharpeville Massacre (1960) and the Marikana Massacre (2012) - to explore how these tragedies connect to their British predecessors across time and space, revealing the continuous nature of the struggle for human dignity and rights.

Sharpeville: Echoes of Peterloo

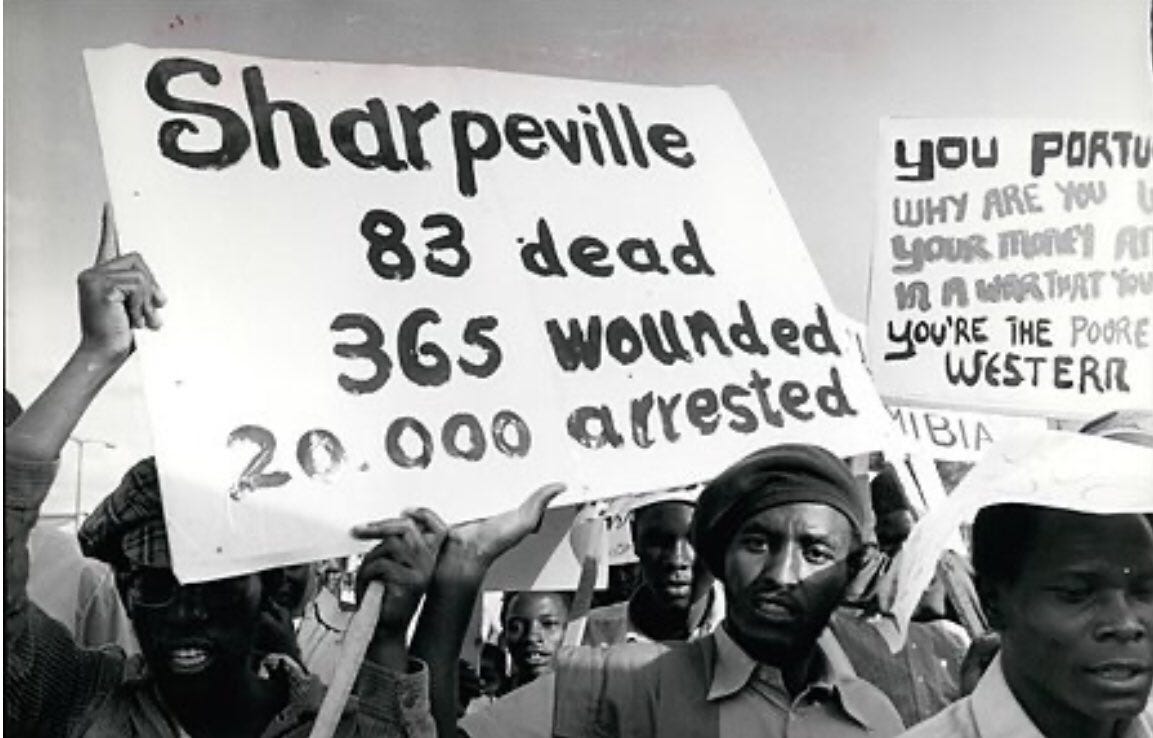

On 21 March 1960, in the township of Sharpeville, South Africa, approximately 5,000 to 7,000 people gathered for a peaceful demonstration against the country's pass laws - a cornerstone of the apartheid system that controlled the movement of Black South Africans. Like the demonstrators at St. Peter's Field in Manchester 141 years earlier, these protesters came to make their voices heard through non-violent means.

The response from the authorities mirrored Peterloo in its disproportionate violence. Police opened fire on the unarmed crowd, killing 69 people and wounding 180 others. Many victims were shot in the back while attempting to flee. The average victim was hit by eight bullets.

Just as the Manchester authorities justified their actions by citing fears of revolution, the South African police claimed they acted in self-defence against a threatening mob. And just as with Peterloo, subsequent investigations revealed a far different reality, one of unnecessary and excessive force against peaceful demonstrators.

The aftermath of Sharpeville, like Peterloo, saw an immediate government crackdown. The apartheid regime declared a state of emergency, banned opposition organisations including the African National Congress (ANC) and Pan African Congress (PAC), and arrested thousands of people. Yet, also like Peterloo, the massacre ultimately strengthened rather than weakened resistance, becoming a catalysing moment that intensified international condemnation of apartheid and galvanised the liberation movement.

Marikana: Modern-Day Tolpuddle

The Marikana Massacre occurred on 16 August 2012 near the Marikana platinum mine in South Africa's North West Province. Like the Tolpuddle Martyrs who organised for better wages against powerful agricultural interests, the Marikana miners were engaged in a wildcat strike demanding improved pay and working conditions from Lonmin, a powerful multinational mining corporation.

The striking miners, living in informal settlements with inadequate sanitation and limited access to clean water, were earning approximately R4,000 (£250) per month for dangerous work in the platinum mines. Their demand for a living wage of R12,500 (£780) was deemed unreasonable by Lonmin executives, some of whom earned millions annually.

When the South African Police Service moved to disperse the miners gathered on a nearby hill, they opened fire with automatic weapons, killing 34 miners and wounding 78 others in the most lethal use of force by South African authorities since the apartheid era.

Like the Tolpuddle case, Marikana revealed the uneven power dynamics between organised workers and economic elites, with the state often siding with capital against labour. In both cases, workers seeking basic dignity and fair compensation faced severe consequences for their organising efforts.

Connections Across Time and Space

These four events, spanning nearly 200 years and two continents, reveal remarkable similarities:

Peaceful gatherings met with lethal force: In all four cases, people assembled peacefully to voice legitimate grievances, only to face violent suppression.

State power protecting economic interests: Whether Manchester's textile industry, Dorset's agricultural landowners, apartheid's racial capitalism, or modern South Africa's mining sector, state violence often serves to protect the economic status quo.

Criminalisation of dissent: From the Six Acts following Peterloo to the state of emergency after Sharpeville, authorities responded by further restricting rights rather than addressing underlying grievances.

Class and race as intertwined factors: While British cases emphasised class divisions and South African events had explicit racial dimensions; both reveal how power systems use available social divisions to maintain control.

Martyrdom as catalyst: In each case, the bloodshed and suffering became powerful symbols that strengthened rather than weakened movements for justice.

Wider Lessons

What might these four tragedies, separated by time and geography yet connected by pattern, teach us?

Rights are never freely given: From voting rights in 19th century Britain to racial equality in South Africa, meaningful rights are rarely granted without pressure from below. The powerful rarely relinquish privilege voluntarily.

Violence often precedes change: Tragically, significant social advances frequently follow bloodshed, as if societies require sacrifice before acknowledging injustice. Peterloo contributed to electoral reform, Tolpuddle to trade union rights, Sharpeville to international anti-apartheid sentiment, and Marikana to renewed attention on post-apartheid economic inequality.

Official narratives mislead: In all four cases, initial official accounts portrayed victims as aggressors and authorities as restorers of order. Only persistent counter-narratives from witnesses, journalists, and historians eventually established more accurate accounts.

Progress isn't linear: The direct line from Sharpeville (1960) to Marikana (2012) demonstrates that gains in political rights don't automatically translate to economic justice. South Africa ended apartheid but preserved many economic structures that maintain inequality.

Solidarity transcends borders: International pressure proved essential following both Tolpuddle and Sharpeville. The imprisonment of the Tolpuddle Martyrs generated petitions with 800,000 signatures, while Sharpeville prompted global condemnation and eventually sanctions against the apartheid regime.

Remembrance as Resistance

These massacres persist in collective memory not merely as historical footnotes but as living touchstones of ongoing struggles. The annual Tolpuddle Martyrs Festival in Dorset, commemorations at Peterloo in Manchester, Sharpeville Day (now Human Rights Day) in South Africa, and memorial events at Marikana all serve to connect past sacrifices with present challenges.

Remembering these events becomes itself an act of resistance against the erasure of ordinary people's struggles. While official histories might prefer to forget such uncomfortable episodes, communities keep these memories alive as testimony to both the price of justice and the unfinished nature of the fight.

Conclusion

The line connecting Peterloo (1819) to Marikana (2012) runs unbroken through Tolpuddle (1834) and Sharpeville (1960). Each represents a moment when those without power stood against those with it, demanding recognition of their fundamental humanity, whether as citizens deserving political voice, workers entitled to fair compensation, or human beings worthy of equal treatment regardless of race.

These events matter not only for understanding history but for interpreting our present. When we witness contemporary movements for justice, whether demanding racial equality, fair wages, climate action, or democratic representation, we see the same essential struggle continuing. Different actors on different stages, but the same fundamental human story of resistance against systems that deny dignity to some while privileging others.

The lessons of these four tragedies suggest that rights and dignities are never permanently secured but must be continually defended. Yet they also offer hope that solidarity, persistence, and collective action can eventually bend the arc of history toward justice, however high the cost.