Introduction

Everyone, whether they realise it or not, operates based on a theory of how the world works. This notion aligns well with the concepts discussed in Cabral's "Weapon of Theory" and merits further exploration. In our day-to-day lives, we all make decisions and take actions guided by our understanding of cause and effect. This understanding, though often unexamined, forms the basis of our personal theories about reality. These theories shape our worldviews, influencing how we interpret events and navigate our surroundings.

Our unconscious biases, too, can be seen as unofficial theories about different groups or situations. These biases colour our perceptions and behaviour without our conscious awareness. Similarly, the cultural norms we adhere to are essentially shared theories about proper conduct, social structure, and values, often internalised from a young age. What we often dismiss as mere 'common sense' is, in fact, a set of widely accepted theories about how things work or ought to work. Our political and social stances, likewise, are grounded in theories about society, economics, and human nature, even if we don't explicitly frame them as such.

Everyday Theorists

Consider Jane, a primary school teacher in Manchester. She may not think of herself as a theorist, but her approach to classroom management, teaching methods, and student engagement are all based on her theories about child development, learning, and social dynamics. When Jane adjusts her teaching style based on what works for different students, she's refining her educational theories in real-time.

Or take Raj, a local cricket club captain. His strategies for team selection, training routines, and match tactics are all grounded in his theories about sports psychology, physical fitness, and team dynamics. As Raj gains experience and learns from both victories and defeats, he's developing and applying theory in a very practical way.

Even in our personal relationships, we operate based on theories. When Sarah decides to give her partner space after an argument, she's applying a theory about conflict resolution and emotional processing. As she observes the outcomes of such decisions over time, Sarah is continually refining her personal theory of relationships.

From Personal to Political

Cabral's insights become particularly relevant when we consider how these personal theories scale up to societal level. Our individual theories about fairness, justice, and social organisation collectively shape our communities and institutions.

For instance, a community's response to local issues like housing shortages or educational inequalities is shaped by the collective theories held by its members about social responsibility, economic fairness, and the role of government. In Birmingham, a group of residents campaigning for more affordable housing are, in essence, challenging existing theories about urban development and proposing alternative ones.

In the workplace, employees advocating for better conditions are, in essence, challenging existing theories about labour relations and proposing alternative ones. When workers at a factory in Glasgow push for improved safety measures, they're applying theories about workers' rights and corporate responsibility.

Even in our engagement with global issues, such as climate change or international conflicts, our responses are guided by our theories about environmental science, geopolitics, and collective action. A group of students in London organising a climate strike are applying theories about civil disobedience, public awareness, and environmental policy.

The Power of Conscious Theory

As we shall see Amilcar Cabral's work suggests that recognising and developing our theories isn't just an academic exercise—it's a vital tool for personal empowerment and social transformation. By understanding that we all operate based on theories, we can start to question those theories, seek out new information, and make more conscious choices about how we engage with the world around us.

For example, a small business owner in Cardiff might reassess their theories about customer service and community engagement, leading to changes that benefit both their business and the local community. A local councillor in Edinburgh might challenge their assumptions about urban planning, leading to more inclusive and sustainable development policies. In essence, theory isn't just for academics or revolutionaries—it's an integral part of how we all make sense of and interact with the world around us. Recognising this can be a powerful step towards more conscious and effective engagement with our personal lives, our communities, and our broader social and political realities.

By embracing our role as everyday theorists, we can become more active participants in shaping our lives and our societies. We can move from being passive recipients of others' theories to active creators and critics of the ideas that guide our world. This shift in perspective, inspired by thinkers like Cabral, opens up new possibilities for personal growth, community engagement, and social change—all starting from the simple recognition that theory is already an integral part of our daily lives. Whether we're making decisions about our careers, our relationships, our communities, or our planet, we're all theorists. By becoming more conscious of this fact, we can harness the power of theory to create positive change in our lives and in the world around us. This is the enduring relevance of Cabral's insights—not just for revolutionaries or academics, but for all of us in our everyday lives.

This perspective lends weight to Cabral's emphasis on the critical examination and development of theory. If everyone indeed possesses a theory, then becoming conscious of and critical towards our theories becomes crucial for effective action and social change. It suggests that a significant part of the work for activists and revolutionaries involves not only developing new theories but also helping people become aware of, question, and potentially revise their existing implicit theories.

In essence, theory isn't just the domain of academics or revolutionaries—it's an integral part of how we all make sense of and interact with the world around us. Recognising this can be a powerful step towards more conscious and effective engagement with our social and political realities.

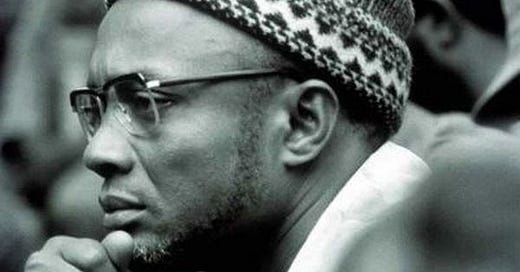

Amilcar Cabral

Amilcar Cabral was a leader of the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde (PAIGC), that waged an armed struggle against Portuguese colonial rule during the 1960’s and 1970’s. His "Weapon of Theory" speech was his address to the delegates of the First Tricontinental Conference of the Peoples of Asia, Africa and Latin America, which took place in Havana, Cuba, in January 1966. The conference was a significant gathering of representatives from various national liberation movements, socialist countries, and anti-imperialist organisations from the three continents. In order to fully understand the speech, one has to know something about the political context that prevailed during this period.

The context of the speech was shaped by the following factors:

· Decolonisation and national liberation movements: The 1960s saw a wave of decolonisation across Africa, Asia, and Latin America, with many countries fighting for independence from colonial powers.

· Cold War tensions: The conference took place in the context of the Cold War, with many liberation movements aligning themselves with socialist countries like the Soviet Union and China, while the United States and other Western powers supported colonial and neo-colonial regimes.

· The Cuban Revolution: The conference was held in Cuba, which had recently undergone a socialist revolution led by Fidel Castro. Cuba's example inspired many revolutionary and anti-imperialist movements across the three continents

· Tri continentalism: The conference aimed to foster solidarity and cooperation among the peoples of Asia, Africa, and Latin America in their common struggle against imperialism, colonialism, and neo-colonialism. It sought to develop a shared theoretical framework and practical strategies for achieving national liberation and social justice.

Cabral's speech, therefore, was not only a reflection on the specific struggle of the PAIGC but also a contribution to the broader discourse on national liberation, anti-imperialism, and socialist revolution that characterised the Tricontinental Conference and the global environment.

The Weapon of Theory

The main idea in the speech is that theory, when properly applied to the specific conditions of a given society, can be a powerful weapon in the fight for national liberation and social justice. Cabral emphasises the importance of theory in guiding the struggle for national liberation, arguing that a thorough understanding of the specific historical, social, and economic conditions of a given society is necessary for devising effective strategies for liberation. He discusses the nature of imperialism and neo-colonialism, highlighting how these systems exploit and oppress the peoples of Africa, Asia, and Latin America, and stresses the need for a united front against these forces. Cabral asserts that culture is a crucial element in the fight for national liberation, arguing that the colonisers often attempt to suppress or eradicate the indigenous culture of the colonised people, and that reclaiming and celebrating this culture is an essential part of the liberation process.

While acknowledging the significance of national liberation, Cabral also emphasises the importance of class struggle within the colonised society, arguing that the struggle against imperialism must be accompanied by a struggle against internal class exploitation. Finally, Cabral calls for unity and solidarity among the oppressed peoples of the world in their struggles against imperialism and neo-colonialism, stressing the importance of learning from each other's experiences and supporting one

Cabral's emphasis on the role of theory in national liberation struggles is rooted in his belief that a deep understanding of the specific conditions of a given society is essential for developing effective strategies for change. He argues that theory should not be viewed as an abstract or academic exercise but rather as a tool for guiding practical action.

For Cabral, the starting point for any national liberation struggle must be a thorough analysis of the specific historical, social, and economic conditions of the society in question. This analysis should encompass factors such as the nature of the colonial or neo-colonial system, the class structure of the society, the state of the productive forces, and the cultural and ideological formations that shape people's consciousness.

Only by understanding these specific conditions, Cabral argues, can activists and revolutionaries develop strategies and tactics that are tailored to the unique challenges and opportunities of their particular struggle. He warns against the uncritical adoption of theories or strategies that may have worked in other contexts but may not be suitable for the specific conditions of a given society. At the same time, Cabral does not discount the value of learning from the experiences of other struggles and movements. He encourages activists to study the theories and practices of other national liberation struggles, both successful and unsuccessful, in order to draw lessons and insights that can be adapted to their own contexts.

Cabral's emphasis on the importance of theory is also tied to his belief in the power of ideas to shape social reality. He argues that the dominant ideas in any society are those of the ruling class and that part of the task of national liberation is to challenge and transform these ideas. This requires the development of a counter-hegemonic ideology that can mobilise the masses and guide the struggle for liberation. In this sense, Cabral sees theory not as a purely intellectual exercise but as a weapon in the struggle for social and political change. By arming themselves with a deep understanding of their own reality and a vision of a new society, activists and revolutionaries can more effectively challenge the dominant system and build a movement capable of achieving national liberation.

I maintain that Cabral's emphasis on the role of theory in national liberation struggles remains relevant for contemporary movements. While the specific conditions of today's struggles may differ from those faced by Cabral and his comrades, the need for rigorous analysis, strategic thinking, and ideological clarity remains as pressing as ever. By engaging in a critical and creative dialogue between theory and practice, contemporary movements can develop more effective strategies for challenging oppression and building a more just and equitable world.

Ideas That Shape Our World: A Journey Through Everyday Theory

Imagine you're walking down the high street of any town in Britain. You pass by shop windows displaying the latest fashions, adverts promoting the newest gadgets, and posters for upcoming films. Without realising it, you're being exposed to a web of ideas about what's desirable, normal, and important in our society. This is what Italian thinker Antonio Gramsci called 'cultural hegemony' - the way those in power shape our everyday thoughts and beliefs.

Take Sarah, a schoolteacher from Manchester. She's always felt a bit self-conscious about her curly hair, spending hours straightening it each week. But why? The answer lies in the subtle messages she's absorbed from magazines, TV shows, and even well-meaning friends about what 'professional' hair looks like. This is cultural hegemony at work in Sarah's daily life.

Now, let's hop over to Bristol, where Jamal, a young activist, is organising a community event celebrating Caribbean culture. Jamal's actions echo the ideas of Amilcar Cabral, an African revolutionary who fought against Portuguese colonialism. Cabral believed that reclaiming and celebrating one's culture was a powerful way to resist oppression. For Jamal, organising this event isn't just about having fun - it's about fostering pride in a heritage that's often overlooked or devalued in mainstream British society.

Meanwhile, in a small flat in Glasgow, Aisha is grappling with feelings of anxiety and self-doubt. As a hijab-wearing Muslim woman, she often feels out of place in her workplace. Aisha's experience resonates with the writings of Frantz Fanon, who explored how being part of a marginalised group can affect one's mental health and self-image. By recognising these feelings as a result of societal pressures rather than personal failings, Aisha is taking the first step towards overcoming them.

In a community centre in Cardiff, a group of pensioners are attending a talk about Britain's colonial history. The speaker, inspired by the work of Walter Rodney, is explaining how understanding the past can help us make sense of current global inequalities. For many attendees, this is eye-opening information that changes how they view the world and Britain's place in it.

These seemingly disparate scenarios - Sarah's hair struggles, Jamal's cultural event, Aisha's workplace anxieties, and the history talk in Cardiff - are all connected by the thread of ideas put forward by thinkers like Gramsci, Cabral, Fanon, and Rodney. Their theories help us understand how power operates not just in parliament or boardrooms, but in our everyday lives, shaping our thoughts, feelings, and actions in ways we often don't notice.

But understanding these ideas isn't just an academic exercise. It's a tool for change. When Sarah decides to wear her hair naturally to work, she's challenging cultural hegemony in a small but significant way. Jamal's event isn't just a celebration - it's a form of resistance against cultural erasure. Aisha, by recognising the societal roots of her anxiety, can begin to challenge those feelings and the structures that cause them. And the pensioners in Cardiff, armed with new historical knowledge, might view current events with a more critical eye.

These everyday acts of questioning and challenging 'common sense' ideas are the building blocks of broader social change. They're what Gramsci called a 'counter-hegemony' - a new set of ideas and values that can gradually shift what society sees as normal or desirable.

So, the next time you're walking down that high street, take a moment to question the messages you're seeing. Why are certain body types or lifestyles being promoted? Whose stories are being told in the books displayed in the shop window? By asking these questions, you're not just being curious - you're engaging in the kind of critical thinking that these thinkers saw as essential for creating a fairer world.

In the end, the ideas of Gramsci, Cabral, Fanon, and Rodney aren't just theories gathering dust on library shelves. They're living, breathing concepts that can help us understand and change our world, one small action at a time. Whether it's choosing how to wear our hair, celebrating our heritage, understanding our mental health, or learning about history, we're all theorists in our everyday lives. And that's a powerful thing indeed.

Relevance

Many of the lessons and ideas put forth by Amilcar Cabral in his "Weapon of Theory" speech remain relevant to contemporary struggles for social justice, equality, and self-determination. Some of these lessons include:

1. The importance of theory and analysis: Cabral stressed the need for a deep understanding of the specific historical, social, and economic conditions of a given society in order to develop effective strategies for change. This lesson remains relevant today, as activists and movements must continually analyse and adapt to the complex realities of their struggles.

2. The interconnectedness of struggles: Cabral called for unity and solidarity among the oppressed peoples of the world, recognising that their struggles against imperialism, racism, and exploitation were interconnected. In today's globalised world, this lesson is perhaps even more relevant, as the challenges faced by marginalised communities across the world are often rooted in similar systems of oppression.

3. The role of culture in resistance: Cabral emphasised the importance of reclaiming and celebrating the indigenous cultures that colonisers sought to suppress or eradicate. This lesson resonates with contemporary struggles around cultural identity, representation, and the decolonisation of knowledge and cultural spaces.

4. The need to address internal inequalities: While focusing on the fight against external oppression, Cabral also highlighted the importance of addressing internal class inequalities within the colonised society. This lesson remains relevant for contemporary movements, which must grapple with intersecting forms of oppression and work to build more just and equitable societies.

5. The power of collective action: Cabral's emphasis on the need for unity and solidarity among oppressed peoples underscores the power of collective action in bringing about social change. Contemporary movements, from Black Lives Matter to climate justice campaigns, continue to demonstrate the importance of building broad-based coalitions and mobilising collective power.

6. The role of leadership and organisation: Cabral's own role as a leader of the PAIGC highlights the importance of committed principled leadership and effective organisation in the struggle for liberation. Contemporary movements continue to grapple with questions of leadership, democracy, and organisational structure as they work to build sustainable and effective vehicles for social change.

While the specific contexts of contemporary struggles may differ from those faced by Cabral and his comrades, the underlying principles of unity, analysis, cultural resistance, and collective action continue to offer valuable guidance for those working to build a more just and equitable world.

Conclusion

In this journey through the landscape of everyday theory, we've explored how the ideas of thinkers like Cabral, Gramsci, Fanon, and Rodney manifest in our daily lives. From Sarah's hair choices to Jamal's community event, from Aisha's workplace struggles to the pensioners' history lesson, we've seen how these seemingly abstract concepts shape our personal experiences and societal structures. This Letter has aimed to demystify complex theories, showing their relevance beyond academic circles and their power in our hands as ordinary people. Moving forward, we can use these insights to question the 'common sense' ideas that surround us, to recognise the value in our diverse cultures and experiences, and to understand how our personal challenges often connect to broader social issues. By becoming more conscious of the theories that guide our lives, we equip ourselves with powerful tools for personal growth and social change. Whether it's challenging beauty standards, celebrating cultural heritage, addressing workplace inequalities, or re-examining historical narratives, we all have the capacity to be 'everyday revolutionaries'. The next time you make a decision, big or small, remember you're not just living your life, you're putting theory into practice. And that's how change begins.